In my review of The Spiral Staircase, I mentioned Douglas Brode’s Edge of Your Seat: The 100 Greatest Movie Thrillers, and that I expected I would soon be getting to #61 on that list, Roger Corman’s adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Pit and the Pendulum.” It is the only film from Corman to make the list, and although I am reviewing it last in my Corman/Poe series of reviews, it’s notable that this was only the second of these adaptations, following House of Usher by about a year. It was itself followed by Premature Burial, and having viewed those out of order, I made a joke in my Usher review that it and Burial follow a fairly similar and specific sequence of events. I’m glad I didn’t watch them in release order, because I might have given up on Burial, given that Pendulum follows almost the exact same stations of the plot.

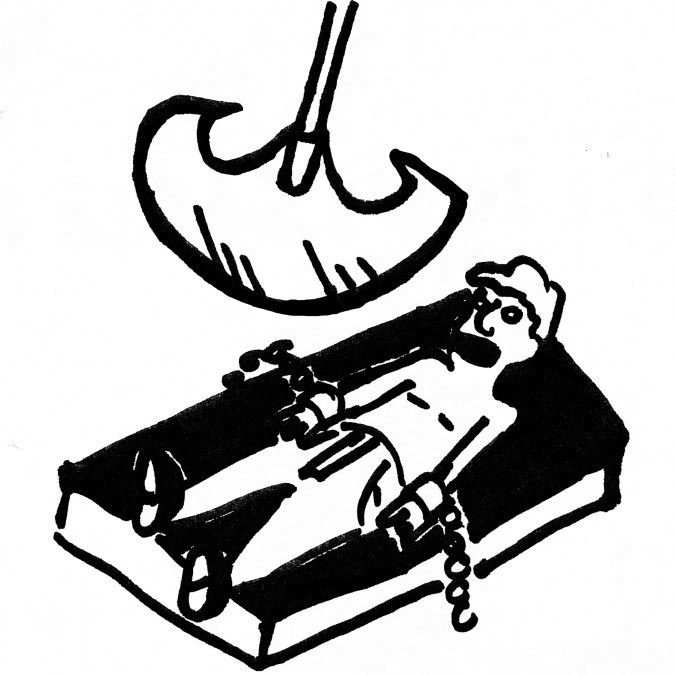

As the film opens, a man approaches a seaside castle (different from Usher and Burial in that the character does not approach the lead’s home from across a foggy moor), knocks upon the door and demands to see the home’s owner, and is initially rebuffed by the servant who answers the door, but is then allowed in to the home by the sister of Vincent Price’s (and in the case of Burial, Ray Milland’s) character. It’s genuinely shocking that so little effort was made to differentiate this from its immediate predecessor, and that the film that immediately followed would adhere so closely to the same structure. Here, our hero is Francis Barnard (John Kerr), who has come to see the widower of his late sister Elizabeth (Barbara Steele). He is allowed entry by his sister-in-law, the Donna Catherine Medina (Luana Anders), who tells him that her brother Don Nicholas (Price) is resting, but allows him inside nonetheless. Barnard asks to see his sister’s grave, but Catherine tells him that she is not buried in some churchyard and is instead interred in the crypts beneath the castle; as she escorts him to Elizabeth’s resting place, the two pass another room in the catacombs from which a great racket emerges. Nicholas exits the door and tells Barnard that it conceals a contraption, the ceaseless operation of which he is responsible for.

Although the Medinas are reticent to reveal every detail of Elizabeth’s death, the arrival of family friend Dr. Leon (Antony Carbone) leads him to drop some information that prompts Barnard to demand explanation. As it turns out, although theirs was a good and loving marriage, Nicholas’s beloved bride was ultimately affected by the evil that is present in the Medina estate, as Nicholas and Catherine’s father, Sebastian (also Price) was a member of the Spanish Inquisition. An untold number of people were tortured and killed in the castle’s catacombs, where Sebastian’s implements of torture remain. Apparently, the sleepwalking Elizabeth made her way to this chamber and somehow got herself stuck in an iron maiden, and when she awoke there, she died of heart failure from the fright of it all. Of course, Nicholas himself fears that Elizabeth was not truly dead when she was buried (again, just as in Usher and Burial), despite Dr. Leon’s willingness to stake his reputation on his confirmation of her death, and that her spirit haunts the castle as a result. There are spooky things about, after all. Elizabeth would play the harpsichord nightly for her husband, and when the instrument is heard late at night and one of her rings found atop it despite the apparent absence of any people or even a way in or out of the room, it raises questions. A kind of explanation is found when Barnard discovers a series of secret passageways that connect locked rooms to Nicholas’s own chambers, with Nicholas himself fearing that he may be losing his mind and performing as Elizabeth.

This one is pretty fun, and it probably is the best thriller of Corman’s Poe cycle. I’ve tried to avoid spoilers as much as I can for these but I don’t seem to be able to find a way to talk “around” another of the recurring elements here, so I’ll just have to come right out with it: it’s very strange how often the resolution to the apparent mystery is that Vincent Price’s character’s wife isn’t as in love with him as he was with her, and also that reports of her death are greatly exaggerated. As in The Raven, we’re never given any reason to think that Elizabeth here, Lenore there, or Emily in Burial are anything other than the loving, adoring spouses that they appear to be, until the sudden revelation that all of the gaslighting being performed against the lead is being done by his wife. And it’s Hazel Court two of those times! (She also appeared in Masque of the Red Death, but her villainous nature is on display from her first moment on screen therein.) It stands to reason that making eight of these movies in four years would be bound to lead to some recycling of plots, especially given that the specific Poe works being “adapted” also have large Venn diagram overlaps in their narratives, but viewing this one as the finale in an attempt to save the best for last ends up doing it a disservice. It’s not a bad movie, but it feels repetitive, which isn’t fair to hold against Pendulum because it was only the second one of these that Corman made and is thus responsible for setting the standard which was copied, not vice versa. But hey, at least the Medina castle doesn’t get burned to the ground at the end.

One of the recurring elements present here that really works is the use of the oversaturated nightmare sequence, although here it’s more of an oversaturated flashback. As Nicholas reveals the details of the halcyon days that he and Elizabeth had together, everything is bathed in greens and blues, which turn to purple when Elizabeth “takes ill.” There’s also a fun iris-in transition to this flashback, which happens again when Catherine reveals to Barnard that Nicholas actually bore witness to the murder of his mother and uncle Bartolome at the hands of their father, who discovered his wife and brother were adulterers. In this sequence, the saturation color turns to a bloody, angry red, and it works remarkably well. (For those like me whom I would lovingly refer to as “Belle & Sebastian-pilled,” think of it as going from the cover of The Boy With the Arab Strap to Write About Love to If You’re Feeling Sinister.) Of course, this all comes back around when it’s revealed just who’s behind everything, only for Nicholas to fall backward down some stairs in fright at the sudden reappearance of Elizabeth and, concussed (or more), descends into the belief that he is Sebastian and that Elizabeth and her lover are the late Mrs. Medina and Bartolome and exacts his revenge accordingly, not entirely unlike Dexter Ward being overtaken by the spirit of his ancestor in The Haunted Palace.

Another notable element of these, now having seen all of them, is how variably effective they work as mystery thrillers. Other than Masque with its large ensemble, the cast of all of these films has been relatively small, in line with Corman’s notoriously spendthrift nature. As a result, the extremely limited number of characters can curtail the film’s ability to provide sufficient red herrings or otherwise conceal the identity of the film’s villain or villains. Pendulum certainly does the best job of keeping one guessing as to what’s really happening in the stately mansion in which all the events occur, playing things close enough to the vest that the reveal of Elizabeth’s co-conspirator feels satisfying but not obvious. That’s probably why Brode selected this one for inclusion in Edge of Your Seat, even though I wouldn’t call this the best of the Corman-Poe cycle overall. In his “also recommended” section, however, I found that he agreed with me overall, writing “Among the other Poe adaptations, by far the best two are The Masque of the Red Death […] and Tomb of Ligeia,” the latter of which he calls “an intelligent, restrained suspense tale.”

You may be asking yourself where the pendulum is in all of this, or the pit, for that matter. For that, my friend, you will have to watch for yourself.

-Mark “Boomer” Redmond