There’s an awkward transition period between silent and sound pictures, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail sits right in the middle of it. In fact, it straddles the line between the two. If you look up the film online and click the first streaming link that your search results present, you’ll find yourself watching the film in sound, but this was actually a late-breaking change made well into production. The Kino Lorber DVD release that my library has contains both the silent and the talkie versions of the film, and the silent one was actually more financially successful in its day than the other — largely due to the fact that most British cinemas didn’t have sound technology installed yet, reducing the talkie Blackmail’s overall box office. Blackmail stands at this crux in the leap in film technology, and so we must give it some grace for its issues.

Flapper Alice White (Anny Ondra) is dating Scotland Yard detective Frank Webber (John Longden), although she finds him a bit of a bore. On the side, she’s also occasionally going on dates with a painter named Crewe (Cyril Ritchard). After an argument at a tea house, Frank storms out, allowing Crewe to offer to take Alice out, and Frank sees the two leaving together. Crewe takes Alice to his artist’s loft and the two flirt for a bit before Alice volunteers to wear a (for the time) racy dancing costume and model for Crewe; he hides her clothes while she’s changing and his personality drastically changes as he attempts to force himself on her. Alice manages to grab a nearby knife and kill Crewe in self-defense, but she goes home in a state of shock. The following day, reminders of Crewe’s death are all around her, and a gossipy neighbor standing about in her father’s newsstand recounting the grisly details doesn’t help. Frank visits the scene of the killing and finds one of Alice’s gloves, pocketing the evidence before anyone else sees it and bringing it to her, where she wants to tell him everything but can’t verbalize the horror of her situation the previous night. Unfortunately, Alice’s exit from Crewe’s building was witnessed by career criminal Tracy (Donald Calthrop), who arrives with Alice’s other glove and announces his intent to extort both Alice and Frank.

I’m not entirely certain that calling this film a “thriller” accurately reflects the content. The title act of blackmail doesn’t really enter the narrative until quite late in the game, and although the film’s energy picks up in its final act, the first three quarters of its eighty-five-minute runtime is fairly slow-paced. If anything, the film is more of a character study of Alice White than anything else. The film follows her almost entirely and spends a great deal more time on extended examinations of her face as she reacts to things that happen around her. Ondra has the perfect features for this era of filmmaking, with the big eyes and pouty lips that were best suited to convey the outsized emotions that dialogue-free performance required. Her English was so accented, however, that Hitchcock had another actress (Joan Barry) say Alice’s lines off-camera while Ondra lip-synced the dialogue, and the result is a little uncanny. (This was a technological limitation of the time; in Murder!, released the following year, the main character’s internal monologue while listening to the radio was accomplished by having the actor record his lines and then act along to his own voice on the tape, all while a live orchestra played the music that was supposedly playing on his radio.) That slight awkwardness as a result of this method is a little strange, but it unintentionally adds another layer to the performance, as if Alice’s experiences have left her so out of sorts that she’s not entirely in sync with her own mind.

This is Alice’s story: she’s just a girl wanting to have fun, and she’s bored of her cop boyfriend always taking her to the movies. Crewe, a mysterious artist, shows an interest in her and invites her back to his place, where he shows off his work and even lets Alice express herself on a canvas as well, and it’s all fun and games before he reveals his true intentions. She defends herself but kills him in the process and returns home to wash his blood out of her clothes. On the street, the positions of people at rest remind her too much of the state she left Crewe’s body in, and when she’s trying to have breakfast with her family, she can’t get any peace. Her boyfriend arrives with evidence that she’s been two-timing him and she can’t even speak about the kind of danger that she defended herself from. All of this is before Tracy even enters the picture. This isn’t a thriller, really; it’s a noir, one with an inciting incident that would appear in noirs for decades to come, at least into the fifties with titles like The Blue Gardenia. How much you’re going to be invested in the film depends on how much you like Alice, and although I did, I can see her characterization being a harder pill to swallow for others, even before getting into the strange lip syncing issue that may further turn some viewers off. In the end, Tracy is sought for questioning purely as a matter of having a criminal record and having been in the area, and he flees the police, leading to a chase that winds through the British Museum before he falls from the building’s roof to his death. This leads to Crewe’s death being pinned on Tracy and Alice being free to go, but the film lingers on her face in its final moments in a way that makes it plain that although she may be legally absolved, she’s been forever changed by having to slay a man in order to protect herself from his sexual assault.

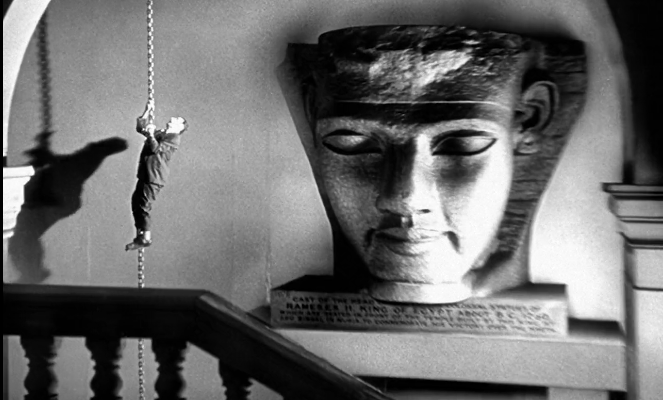

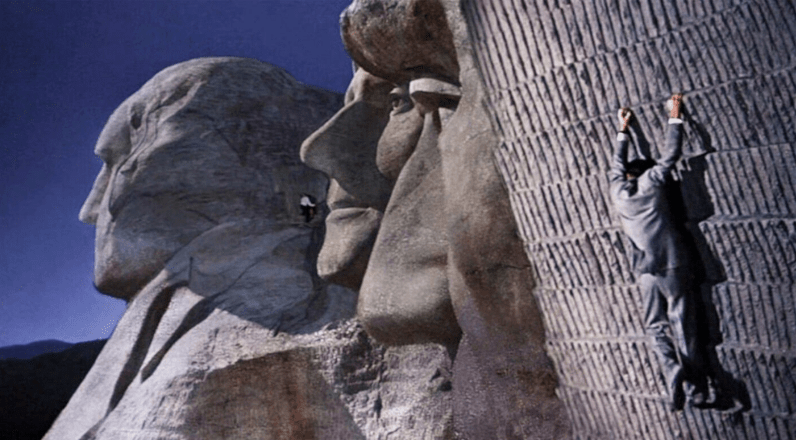

As to the elements that make the film memorable as a Hitchcock text, the final fourth of the film sees Tracy being chased by the police, presaging several images and ideas that would go on to be reliable tricks in the director’s bag. In the British Museum, Tracy descends a rope to escape his pursuers past a giant bust of presumably Egyptian origin. There’s a distinct visual genealogy between this and the finale of North by Northwest:

The Mount Rushmore sequence is also part of another one of Hitchcock’s trademarks, which was to have the film’s final action scenes lead to a rooftop climax, most famously in Vertigo but also To Catch a Thief, Rear Window, and Foreign Correspondent, just to name a few (although for the last two of these Jimmy Stewart is dangled out of a window rather than off of a rooftop and the fall from Westminster Cathedral tower happens at the beginning of the third act rather than its end, respectively). The chase scene through the museum is also clearly echoed in the protracted sequence that concludes I Confess, although this one is stronger and Hitchcock is already demonstrating his strong eye for composition when it comes to setting up the most interesting version of a shot, sticking the camera in the vertices of an oddly shaped room or taking on an overhead view of a large reading area. He’s also already inserting his sly sense of humor into the proceedings. Despite the relative novelty of the art form, the characters within the film are already talking about movies as if the whole enterprise is old hat; Frank seemingly only wants to go to detective flicks which Alice finds boring and predictable, and Frank admits he’s still excited to see the latest one about Scotland Yard, even if “they’re bound to get most things wrong.” Hitchcock’s lack of respect for the institution of the police overall is on display as well, since the entirety of Scotland Yard does, in fact, get most things wrong; they latch onto Tracy based on circumstantial evidence and chase him to his death, unknowingly doing so in order to cover for a killing (albeit a legally defensible one) committed by the girlfriend of one of their own members.

It’s all good stuff, but I doubt that Blackmail remains of much interest even to most film-lovers who don’t have an unhealthy interest in Hitchcock’s body of work. Narratively, it’s not in conversation with his other texts, at least not those we think of as the canonical forty thrillers. Insofar as it’s useful as an interpretative tool for his filmography as a whole, this film feels like an attempt at experimenting with techniques and images that he would perfect later and is fascinating in that right, but I once again fear that this fascination extends only to real Hitch-heads. The Lodger is a much more engaging film if you’re interested in what the director’s silent and silent-adjacent work was like, and for experiments with the artform that sound introduced into the medium, Murder! has more fascinating production trivia and smoother tone overall, although I’d go to bat for Blackmail’s value as a noir character study before I’d recommend the 1930 film. This is in the public domain, so hopefully it’s not too hard for you to find if I’ve sold you on it.

-Mark “Boomer” Redmond