On a recent vacation in the Twin Cities, I spent an afternoon at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, which is currently exhibiting “150 photographs of, by, and for Indigenous people” in a photography collection titled “In Our Hands”. It was during that same vacation when I watched Martin Scorsese’s Indigenous genocide drama Killers of the Flower Moon, which is also a series of photographs grappling with the medium’s representation & othering of Indigenous peoples. Because I’m a movie obsessive, the photographs featured in “In Our Hands” that spoke to me loudest were the ones about misrepresentations of “American Indians” in American pop media. Cara Romero’s 2017 photograph “TV Indians” pairs living Indigenous figures with vintage images of fictional Indigenous stereotypes, displayed on cathode-ray televisions in the colonized & decimated landscape of New Mexico. Sarah Sense’s 2018 mixed-media piece “Custer and the Cowgirl with Her Gun” combines images of vintage Indigenous stereotypes in media with personal photographs & historical writing from her Chitimacha & Choctaw homeland through a traditional basket weaving technique that transforms & reclaims the medium of photography for a culture it has been historically weaponized against. Killers of the Flower Moon also addresses the fraught history of Indigenous representation in American media, to the point where its theatrical exhibition opens with Scorsese explaining his “authentic” behind-the-scenes collaboration with the Osage communities the story depicts. The film also concludes with a second onscreen appearance from the director effectively apologizing for his participation in the tradition of speaking for & about Indigenous people from a white American perspective.

To his credit, Scorsese does limit the amount of time & space he spends speaking for the Osage tribe, smartly focusing instead on the people he’s built an entire artistic career around understanding: white thugs. Killers of the Flower Moon is a typical Scorsese crime picture in that it details the step-by-step villainy of greedy American brutes who commit heinous, organized acts of violence in order to squeeze a few petty dollars out of their neighbors. He acknowledges this continuation of his pet themes by casting his two go-to muses in central roles: Leonardo DiCaprio as a slack-jawed goon and Robert De Niro as the criminal mastermind who puppeteers him. The dastardly duo conspires to become friends, family, heirs, and murderers to the Osage people, who have stumbled upon immense wealth when their government-assigned strip of land proves to be a viable source of crude oil. DiCaprio’s assigned mark is a lonely but stoic young woman played by Lily Gladstone, whom he seduces, marries, creates children with, and then slowly poisons while murdering members of her family under the direction of De Niro’s whims & schemes. Gladstone’s performance is formidable within that central trio, and she stands to benefit the most from this collaboration with Old Uncle Marty. Still, it’s the slimy, bottomless cruelty of De Niro & DiCaprio’s characters that drives most of the scene-to-scene drama, so that Scorsese is telling his own people’s story more than he is speaking for the Osage. Watching the movie in conjunction with visiting the M.I.A.’s “In Our Hands” exhibit raises questions of why these same film production resources can’t be put in the hands of Indigenous artists as well, but that question does little to unravel the specific story Scorsese chose to tell here.

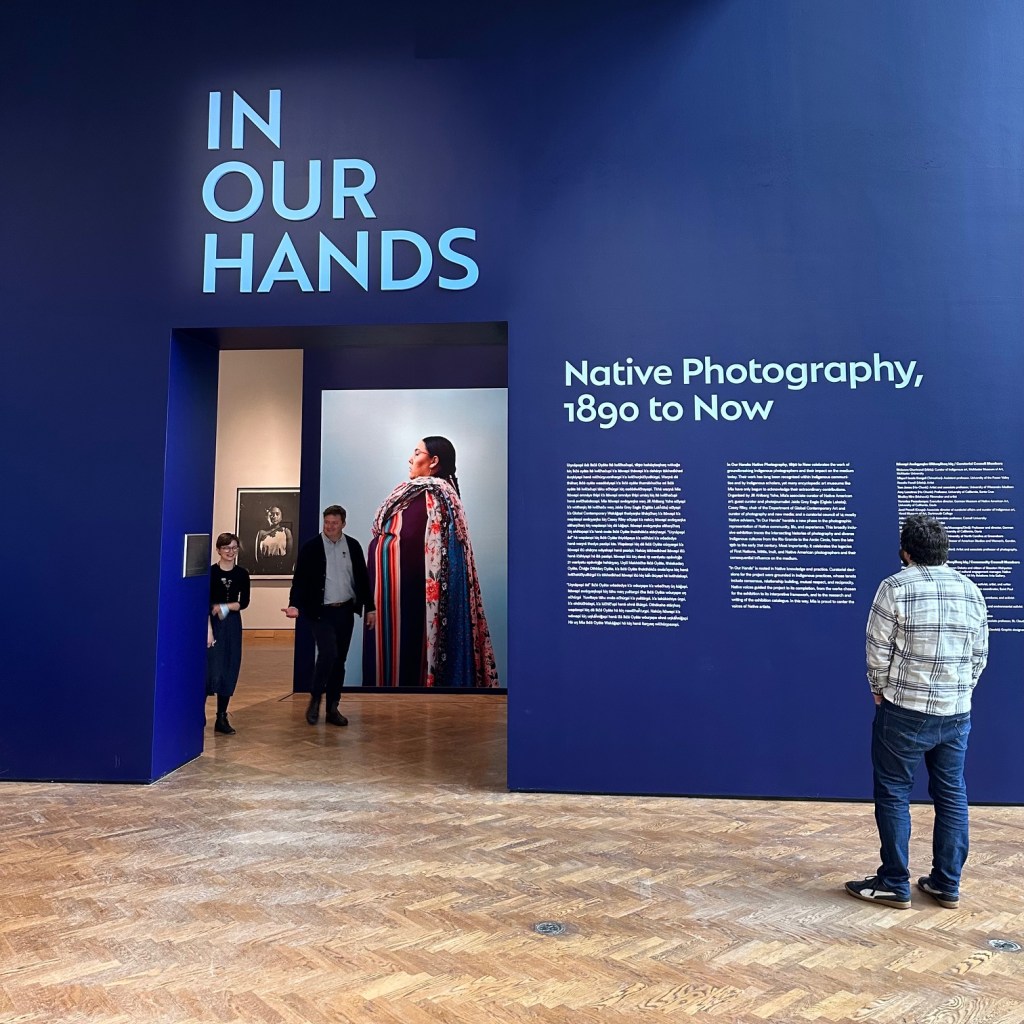

Where the question of authenticity & representation really comes into play is in the film’s coda, delivered after De Niro & DiCaprio’s thugs have already been arrested for their crimes by the Baby’s First Steps version of the FBI. Where lesser Awards Season historical dramas will fill the audience in on how their characters’ lives resolved via onscreen text before the end credits, Scorsese delivers that information via dramatic radio play — complete with the outdat foley sound effects and outdated racist stereotypes that would’ve been contemporary in that pre-cinematic medium. The director then shambles onscreen himself as a radio announcer to read Gladstone’s character’s real-life obituary to the audience with humble solemnity. This is a jarring stylistic swing for a film that often finds Scorsese working in Boardwalk Empire mode more than Goodfellas mode (more dramatic than cinematic), but it’s at least one that seeks artistic purpose beyond reciting this history to a wide audience who needs to hear it. Here we have a quintessentially American story told by a quintessential American storyteller, and yet there’s no way for Scorsese to recite that history without in some way participating in its ongoing genocidal erasure of Indigenous voices. The opening doorway image to the “In Our Hands” exhibit is a portrait of an Osage woman taken by photographer Ryan Redcorn, purposefully representing his subject in a proud, dignified pose. In Scorsese’s picture, Osage women are sickly victims of white American greed, because that’s true to white American history. It’s worth pushing for a better world where both of those images are offered equally accessible platforms, and this film’s coda feels like an uneasy acknowledgement of the current imbalance. Still, this is a story worth reciting, and there are certainly less noble things Scorsese could be doing with $treaming $ervice money than turbocharging Lily Gladstone’s career.

-Brandon Ledet