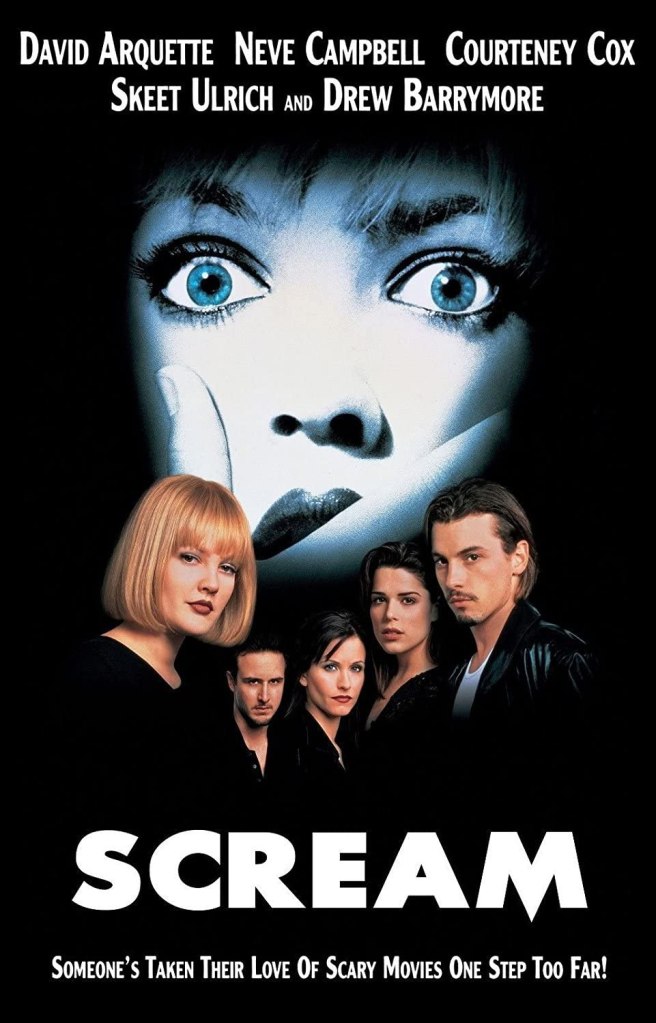

Both of Wes Craven’s mid-90s meta horrors—Scream & New Nightmare—are modern classics, but I personally find the philosophical crisis of his return to the Nightmare on Elm Street series to be the more rewarding of the pair. While Scream amuses itself with cataloging & emulating the tropes of horror as a pop-art medium, New Nightmare genuinely grapples with the havoc horror wreaks on our minds & souls, digging much deeper than Scream‘s surface-level jolts of recognition & nostalgia. For all of their slashings & bloodshed, the scariest moment in either film is when Craven appears onscreen as himself, tormented by the real-world evil he’s unleashed by creating the fictional character of Freddy Krueger. It’s a jarring moment of self-reflection that helped spark an entire wave of self-aware slashers that defined mainstream horror that decade (most of them penned by Kevin Williamson, screenwriter for Scream). Craven wasn’t the first master of horror to arrive attempt that particular hard stare into the mirror, though. He was beaten to the punch by the much trashier & flashier schlockteur Lucio Fulci in his own 1990 meta-horror, A Cat in the Brain.

With A Cat in the Brain, Lucio Fulci stars in a Lucio Fulci film as “Lucio Fulci” — a horror director who’s tormented by the violence he’s depicted onscreen throughout his career, hallucinating flashes of gore while preparing meals and performing mundane household chores. This torment only worsens once his therapist begins to use those gruesome images as inspiration for his own murders, intending to frame Fulci for real-life reenactments of fictional crimes. A rare moment of introspection from the aging giallo legend, A Cat in the Brain is a really fun, chaotic self-reflection on how the brutality of the horror genre is often flippantly overlooked by cheap-thrill seekers but still takes a toll on our psyches (of which I’m just as guilty as Fulci). We can’t fill our brains with images of chainsaw maniacs, squished eyeballs, cannibals, mutant ghouls, and decapitated children without them having some effect on our mental health. Their immediate effect is an easy trigger for cathartic release, usually through laughter or disgust. Here, Fulci frets over the possibility that there may be a morally, spiritually corrosive effect that lingers after that initial amusement . . . or at least he pretends to.

As much as A Cat in the Brain feels like a crude precursor to the philosophy-of-horror crisis Wes Craven would soon be working through in New Nightmare, it’s also just a convenient excuse for Fulci to let his bad taste run wild on a shoestring budget. Firstly, he gets to indulge in the very thing he’s supposedly condemning, padding out the runtime between obligatory dialogue exchanges with as many gory vignettes as he can get away with while maintaining the vaguest outline of a plot. He also comes up with a pretty great excuse not to go to therapy for his horrific preoccupations, positioning his therapist as the real sicko pervert and his own art as a safer, fantastic form of cathartic release. Mostly, he’s engineered an even greater excuse to recycle gnarly gore gags from his own back catalog, “hallucinating” violent scenes from better-loved, better-funded Lucio Fulci movies as if they were specially produced for this late-career meta crisis. A Cat in the Brain isn’t just Fulci’s rough prototype for Wes Craven’s meta-horror; it also doubles as a Greatest Hits montage of his own past triumphs.

If nothing else, you’ve gotta love Fulci for immediately delivering the violence promised by this film’s title in its opening credits, illustrating his thought process at his screenwriting desk with footage of the black cat inside his skull gnawing on the hamburger meat he calls a brain. You also gotta love that he calls himself out for being an absolute freak, even if the resulting self-critique portrait of the maestro at work is entirely insincere. When Wes Craven toyed with “the boundaries between reality & fantasy” in his 1990s meta-horrors, you could really tell he was taking the philosophy & cultural impact of his own work seriously as a subject. By contrast, Fulci is just having self-indulgent fun, even outdoing Scream‘s nostalgic callbacks to classic horror tropes by showing actual clips from better movies of his own heyday. His approach may not be as heartfelt or meaningful, but it’s still a sickly delight.

-Brandon Ledet