When you search for cinematic tourist attractions in Washington D.C., all signs point you towards Georgetown University – the setting and filming location for William Friedkin’s 1973 adaptation of the William Peter Blatty novel The Exorcist. Specifically, they route you to the bottom of “The Exorcist Steps”: the death site of the fictional composite character Father Karras, who launches himself down those horrifically steep steps as a heroic act of suicide at the film’s climax. Given Friedkin’s determination to make the supernatural terror of Blatty’s novel feel as believably authentic as possible, it’s not surprising to learn that the steps are a real location. Referred to as “The Hitchcock Steps” at the time of filming (either in reference to their 19th Century designer, according to Friedkin’s memoir or, more credibly, in reference to the famous 20th Century director, according to locals), they’re a vertigo-inducing connection point between two busy streets at the edge of Georgetown’s campus. The extreme concrete flight burned a hole in Blatty’s mind while he was a student there, as did a local news report about a legitimate, certified exorcism performed in the Washington, D.C. area. The only facts Friedkin had to fudge were minor geographical quibbles that allowed Karras to reach the steps from a nearby window, something that bothered the detail-obsessed filmmaker who wanted to keep his visualization of the novel as accurate as possible. It seems that time has since corrected that adaptational inaccuracy, since there are now several windows facing the concrete staircase that could easily accommodate Karras’s leap. I know this, of course, because I recently visited The Exorcist Steps on a trip to Washington, D.C., despite not being an especially big fan of The Exorcist.

I just find Friedkin’s grounded, real-world approach to supernatural horror to be a little too dry to deliver the genre goods. A lot of people highly regard The Exorcist as one of the all-time greats precisely because it’s “accurate” to the real-world events that inspired it, finding terror in the idea that what it depicts could really happen. I appreciate the tortured domestic drama that results from that approach, especially as a story about two lost adults (Ellen Burstyn as a semi-fictionalized stand-in for Shirley MacLaine and Jason Miller as the doomed Father Karras) desperately looking for a lifeline in a world that no longer makes sense. It’s only after they’ve thoroughly exhausted the scientific, atheistic explanations that could debunk the possibility of demonic possession that Friedkin fully gives in to the supernatural mania of the premise, allowing Linda Blair to literally spew pure evil into the world. Personally, I much prefer the ecstatic mania of The Exorcist‘s two direct sequels, The Exorcist II: The Heretic and The Exorcist III: Legion. That’s where the dark magic of the demonic-possession premise really comes to life, unconcerned with duty to real-world reporting or to Blatty’s writing (despite his continued creative participation in the series). The kinds of audiences who value tasteful restraint over uninhibited entertainment are likely to dismiss the Exorcist sequels outright as silly dilutions of an important, respectable piece of art. Those sequels are exactly what attracted me to visiting The Exorcist Steps in Georgetown, though, since they speak more loudly to my tastes as a horror fanatic who prefers his horror to be fantastic rather than realistic.

So, what most D.C. travel guides tend to gloss over is that The Exorcist Steps are not only significant to the events of the original Exorcist film. They are a constant, chilling presence throughout the initial trilogy, even more iconic to the series than Linda Blair’s spinning head. In The Exorcist, the steps are largely used as an ominous mood-setter, repeatedly presaging Karras’s fall in establishing shots that beckon the in-over-his-head, faith-questioning priest to meet an early end. The Exorcist II also uses them as an establishing exterior to signal that the story has returned to Georgetown. While most of The Heretic is spent detailing young Regan’s life in New York City therapists’ offices—attempting to heal from her demonic episode through radical dream-state hypnosis sessions—it can’t help but drag the audience back to Georgetown at regular intervals, afraid to stray too far away from the familiar details of the original. Each return to Georgetown is established by a shot of the infamous concrete steps . . . except, not really. The Exorcist II was shot on a studio lot in Los Angeles as a cost-saving measure, so all onscreen appearances of The Exorcist Steps are an artificial substitute for the real thing. The genuine, real-life steps reappear in the series’ crown jewel The Exorcist III, though, and without the continued participation of Linda Blair as a now-adult Reagan, the series has no choice but to treat them with total reverence. They’re lovingly framed with music-video smoke machines at exaggerated angles, including several action shots of the camera rolling down each step in a dizzying spectacle from Karras’s tumbling POV. The inciting beheadings at the start of The Exorcist III occur on the 15th anniversary of Karras’s fall down those steps, which get their own reverent shout-out during Brad Dourif’s show-stopping speech as the Devil incarnate. It isn’t until The Exorcist III that The Exorcist Steps truly got their full due as a horror nerd fetish object; it was a slow upward climb to get there.

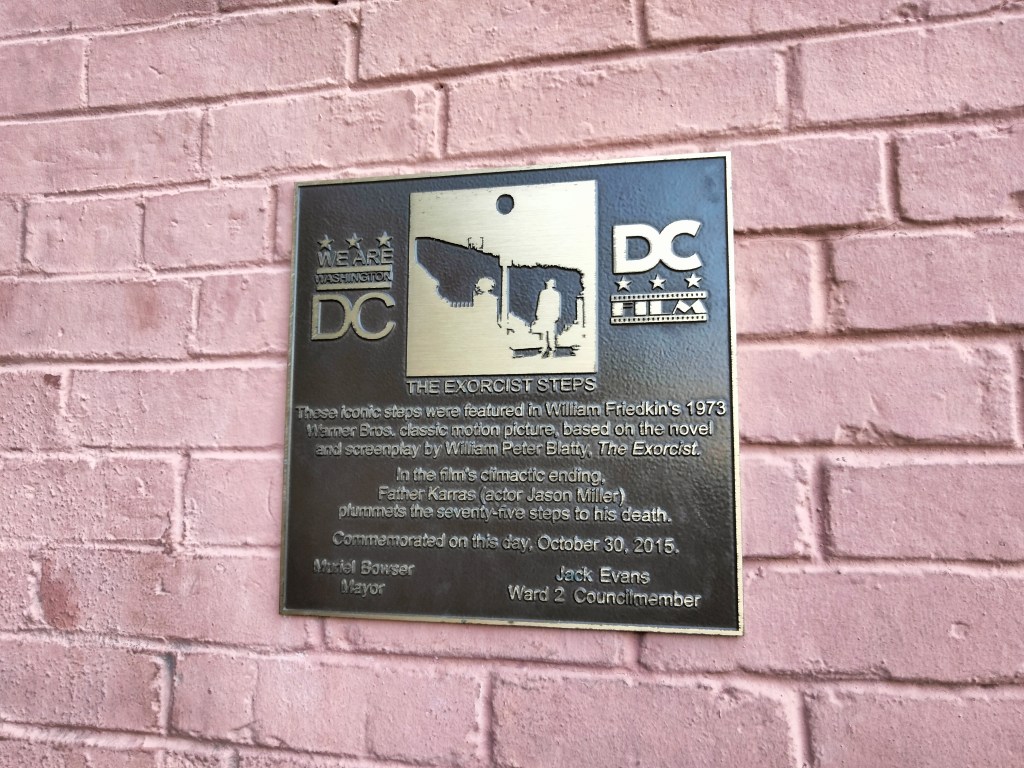

The Exorcist Steps were officially designated as a Washington, D.C. landmark in 2015 with the installation of an informative plaque marking Karras’s death site. Shamefully, there are no mentions of The Exorcist II or The Exorcist III on that plaque, despite their significant contributions to those steps’ legacy. When I visited them on an clammy Monday morning, I was greeted by the exact two kinds of frequent visitors you’d expect to see: a fellow gothy tourist who, like me, was there to take pictures and an annoyed local jogger who was impatient for us to get out of the way of his workout routine zipping up & down the steps. I will share my pictures of the steps and their accompanying plaque below as documentation of the state they’re in as of this posting, in hopes that more joggers will be annoyed by horror movie nerds who happen to read this and will be visiting D.C. in the near future. More importantly, though, I’d like to highlight that The Exorcist Steps’ significance to The Exorcist are thunderously amplified by that film’s own sequels, which are just as much worth rewatching before your visit as the original. There’s even an added bonus to rewatching The Exorcist II before visiting D.C. in that the film also features a lengthy visit to the Natural History Museum, which is one of the city’s other must-visit tourist destinations. Of course, Linda Blair’s tour of the Natural History Museum appears to be the one in New York City, not the one in D.C., but the effect is largely the same, much like how that film’s version of The Exorcist Steps aren’t actually The Exorcist Steps. Let’s take a lesson from Friedkin’s folly and not get too wrapped up in the pursuit of accuracy at the expense of pleasure.

-Brandon Ledet