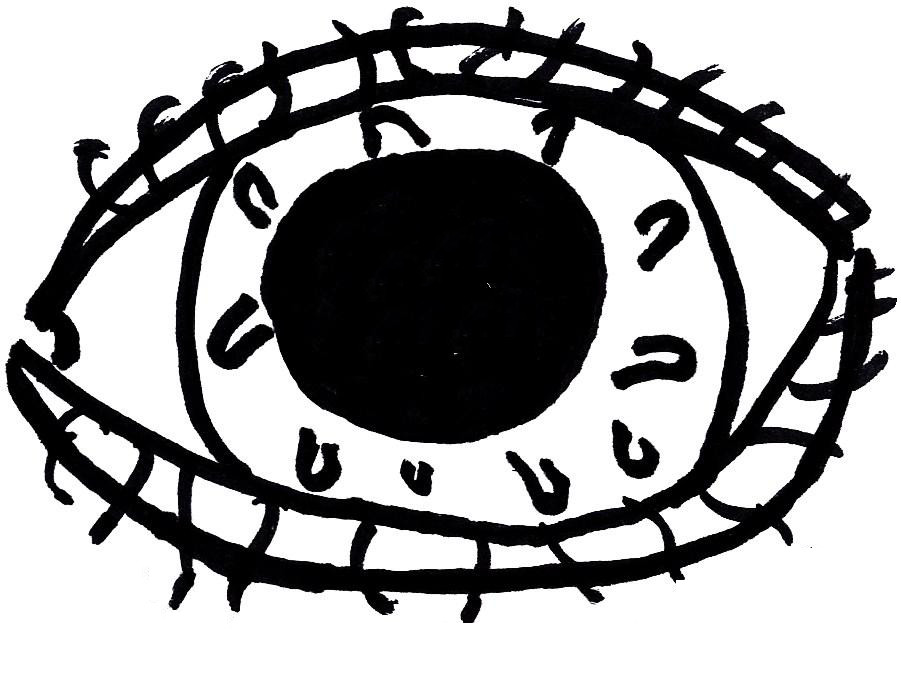

It is a truth non-universally acknowledged that all art is political, but Ash, from director Steven Ellison (better known under his musical moniker Flying Lotus), may be the first film I’ve ever seen that has no identifiable thesis and thus appears to be completely apolitical. This isn’t a criticism so much as an observation of the fact that this movie, despite how much I enjoyed it, seems to be all but completely theme-less. Riya (Eiza González) wakes up, amnesiac, inside of what appears to be crew quarters, surrounded by dead bodies, all of which demonstrate extreme violence done against them. She experiences horrifying flashes of such violence: a head bashed in by a rock, a face melting away as it decomposes, smiles turning from friendly and warm to malevolent and menacing. She walks outside and discovers that she was inside of some kind of station or base on an alien world, as something snowlike drifts down from a sky that is dominated by a radial design that resembles the iris of a great eye, pulsing and pulsating. She sees something vaguely humanoid at a distance, obscured by the harsh atmosphere, although it remains unclear if there is someone or something out there, or if it is perhaps a mirror image of herself (as it mimics her movements) or even a mirage or hallucination. She manages to make it back inside before the atmosphere suffocates her, only to hear a knock at the door. It’s Brion (Aaron Paul), the sixth member of their expedition team, who has left his post in orbit in response to a distress call from the surface, saying that Riya himself had told him that Clarke (Kate Elliott), the only person not accounted for between the two of them and the corpses, had undergone some kind of psychotic break and attacked the others. Riya attempts to recover her memories and advocates for finding and rescuing Clarke, but their time is limited; they have to return to the main spaceship the next time that it completes its orbit in just a few hours, as damage to the base means that they have insufficient atmosphere to wait for it to come around again.

In writing about Lotus’s previous film, Kuso, Brandon noted that the gross out comedy (with heavy focus on the “gross out” part) was of a kind with Adult-Swim-to-feature pipeline films that “tend[ed] to push attention spans to the limit at full length.” I can confirm that this was an issue for one of my viewing companion, who admitted in the car ride on the way home that some of the gaps in his understanding of the film could be attributed to dozing off a couple of times, but this is also a film with an intentionally dense plot that lends itself to few easy answers. The amnesiac protagonist character is not necessarily a new one, but the film initially sets itself up as a bit of a science fiction mystery with an anachronic order: Who killed everyone? Can Brion be trusted? Can Riya, for that matter? As characterization and events are doled out in flashes of recovered memory as well as exploration footage that Riya manages to recover from a drone, we learn more about what happened, and it becomes apparent that this movie is little more than a remix of other films from this genre — an excellently photographed, perfectly soundtracked, and gorgeously colored, to be sure, but a remix nonetheless. That does not detract from the film, but that all of these elements come with a bit of a pacing issue does.

In the opening minutes, as Riya makes her way outside of the base and sees a figure in the distance mimicking her movement, one thinks of the finale of Annihilation. The quick cross-cutting of horrific images in Riya’s mind—be they memories, hallucinations, nightmares, or some combination thereof—calls to mind Event Horizon, which famously tucked all of the visuals that pushed the film into the NC-17 rating into mere blips on screen in order to secure an R, so that the viewer isn’t sure what they’re seeing but are nonetheless disturbed. As Riya watches the video captured by one of the mission’s drones and we intercut between the footage itself and the memories that it awakens within her, one is reminded of the crew of the Nostromo as they approach the downed ship on LV-426 in Alien (that the planet “Ash,” from which the film takes its title, also has a very similar designation is but one of the smallest of many allusions to that franchise). Their discovery of an alien artifact of their own and the realization that this is the first domino that falls before the tragedy we entered in media res at the start of the film is likewise very Alien-like, and then the film pushes further and becomes a bit like Prometheus in the study of organic matter taken from it, which becomes an orifice-invading life form that is ultimately responsible for everything. There’s even a little The Thing in there, as this is an isolated place in a desolate environment where no one can be trusted, as well as a really great Rob Bottin/Stanley Winston style mutant human at the end.

One Alien film it doesn’t borrow from is Alien3, but it does crib from another of director David Fincher’s films, but to say more on that would stray too far into spoiler territory, and I think this is a film that should be gone into with as little foreknowledge as possible. I certainly did; it just happened to be $5 Tuesday (well, $5.75 now) and a friend finally had some time off after having to work an extended stretch of days during and around SXSW. The arthouse was doing repertory screenings of things I had already seen, and Brandon had written about Black Bag and the new Looney Tunes picture, so with nothing more to go on than the tiny icon of the film’s poster in the MoviePass app, I went to the film with a couple of friends. As soon as the characteristic “heartbeat” sound and logo card that accompanies the opening of the Shudder app and precedes the films it distributes, I realized that I had accidentally duped myself into paying for a movie that I could watch at home. That having been said, when the film’s opening fifteen minutes or so felt very much like the beginning of a Syfy Channel original (albeit an extremely elevated and gory one), I was glad that I was watching this in a theater instead of at home, where the film’s pacing would have been a greater challenge on my attention span. This is a film that is introspective, but temporally, not tonally. There’s a lovely dream sequence in the middle that I rather liked, but the purposeful use of long scenes in which very little is happening and we are left to merely contemplate the tableau is something that I can see turning off certain audiences (my two viewing companions, for example, had polar opposite reactions).

Even if you, like me, are more tolerant of those contemplative moments, you may still find that what’s most critically missing here is a lack of theme. Alien is positively (and often literally) dripping with concepts of motherhood, gestation, and birth; The Thing captures a quiet paranoia and isolation that’s universally emotionally applicable; Event Horizon is a parable about madness through the consequences of what happens when science pierces the veil of reality. All of these are existential horrors in what are normally considered environments of speculative fiction, and all of them feature terrifying results of encounters with beings so unlike us that moral concepts of “good” and “evil” don’t really apply. So is Ash. But as to what Ash is about … I’m not really sure that I could tell you. The overall societal decline in attention span has resulted in a lot of discourse about whether a certain scene has a “purpose” or a “point,” meaning to what end does it serve the god of plot and the god of plot alone. Those people are not going to have a good time screening Ash. But the fact that I liked this one so much despite its real lack of theme or thesis tells me that this is a movie with no small amount of things to enjoy and even praise. Its “purpose” is to be an Alien movie unapologetically shot like Knife+Heart; its “point” is to synthesize all of those elements together and then create the best sci-fi synth soundtrack since Blade Runner. It won’t be for everyone, but if you have the inclination after this review to see it, I’d see it on the big screen if you can.

-Mark “Boomer” Redmond