In the Iliad, Patroclus gives a speech about the two jars that sit before Zeus, and from them he dispenses upon humans either gifts or detriments. I like to imagine Guillermo del Toro sitting in one of the enviable throne-like pieces of film memorabilia that fill his home (which he calls “The Bleak House”) and sitting with two jars before him from which he makes his films. One is labelled “Cool,” and it is from this vessel that he dispenses all of his clever ideas, slick visuals, and fascinating character work. From the other, which is labelled “Corny,” he pours in many of the things that his deriders cite as his weaknesses, which is unfair; the resultant cocktail between the two is what matters, and sometimes the stuff that makes it corny is the stuff that makes it great. Not this time, though.

When I texted Brandon (who has a more positive take that you can read here) after leaving the theater with a message that was, essentially, “Oh no, I didn’t like it,” that thread continued into the next day as we discussed that eternal del Toro combination of Corny vs. Cool. Brandon likened it to native English-speaking critics have taken note of actors’ tendencies to go broader in Pedro Almodóvar’s films “of late,” whereas Spanish-speaking critics have stated that this is a matter of perception and that all of his films are like that, it’s just not clear when it’s not in English. And he’s not wrong; we had a similar discussion about Bong Joon Ho’s Mickey 17 being a more “obvious” and less subtle picture than Parasite and how we may simply be viewing them through different lenses unintentionally. For me, however, nothing in any of the performances here is a problem, as they’re all appropriately grave. Of special note are Charles Dance and David Bradley, the former essentially playing Tywin Lannister again (and it’s pitch perfect as always) and the latter playing very strongly against type as a kindly old man, rather successfully. For me, it’s the other choices that make this one feel too tonally inconsistent to be as immersive as it ought to be.

The film is structured as the novel is, with a wraparound story in the glacial north in which a ship captain finds Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac) on the ice and takes him aboard, where the dying man tells his story. Raised by a mostly absent surgeon father (Dance) who was domineering and abusive when he was present, young Victor doted on and was doted upon by his mother (Mia Goth), whose dark hair and eyes she shared with her son and which Victor knew his father despised. When Mrs. Frankenstein dies giving birth to a boy, William, Victor quickly gets relegated to second favorite child, and there’s an abyss between silver and gold, which is exacerbated by Victor’s belief that his father allowed his mother to die; the boys are split up as children following the death of their father and don’t see one another again until adulthood. Victor takes his name literally and seeks to find victory over death, and when we see him as an adult, he is before a hearing at medical school regarding his ghoulish and grisly reanimation attempts. In attendance is Henrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz), whose niece Elizabeth (Goth again) is engaged to William (Felix Kammerer), and who uses this as an excuse to see Victor and offer the virtually limitless resources his war profiteering has given him to fund Victor’s experiments. In all of this, Victor meets Elizabeth and is utterly taken with her, and he begins to engineer reasons to keep her and William apart, and although she is interested in his friendship, she rejects him utterly when he confesses. Amidst this, Victor has been preparing his lab and his patchwork specimen.

Once the monster (Jacob Elordi) is brought to life, Victor at first seems interested in teaching his creation life, but when the being only manages to learn the word “Victor,” Frankenstein becomes impatient and starts to abuse him. After a chance meeting between the creation and Elizabeth and William, Victor floods his laboratory tower with kerosene and destroys it, his last minute regret and attempt to save his “son” leaving him mangled and in need of prosthetic limbs. Interspersed throughout this narrative, we’re also checking in with the ship that Victor is aboard and where he is recounting this story; although the captain believes that they are safe due to the monster having disappeared beneath the ice following a prolonged attack sequence, he reappears and eventually makes his way aboard, where he begins to tell the story from his perspective, and how he sought his vengeance.

There was a little too much of this film that feels like it was shot on The Volume, and I was disappointed by that. This makes sense for the opening sequence, wherein a mass of sailors are attempting to break the ice which has frozen their ship to the surface, only to be set upon by an apparently unkillable monster who goes down hard (and not permanently). It makes less sense when we’re talking about the courtyard outside of Frankenstein’s tower, which sees enough use that it would be a great practical location. Get some styrofoam, carve out some clefts, age it to look like stone, and get a little atmosphere up in this place. Worse still is the tower’s entryway/foyer, which would have looked so good if it had been done practically, but instead kind of looks like someone tried to recreate the Valkenheiser mansion from Nothing But Trouble using the software that rendered the barrel sequence from The Hobbit: Whichever One That Was. The reason for this, of course, is that we need to be able to fill that space with dozens, if not hundreds, of kerosene canisters so we can have our big explosion; that is to say, it has to be disposable, and it looks like it.

It wouldn’t be so out of place if the attention to detail in other places, like Victor’s laboratory filled with previous experiments, which looks like a del Toro dream workshop. The dungeon in which the creation is held is also strikingly imagined, and I like that quite a bit, and we spend enough time in the captain’s quarters that we get to get a real sense of it, and it feels real. Beyond set design (when they bothered), the costume designer went to town on crafting a series of elegant gowns for Mia Goth to wear. They’re all hoop skirts and several have relatively simple sewing designs, but they’re all composed of shimmering fabrics in beautiful patterns like peacock feathers, all in a green hue. Each one is utterly sumptuous, and if there is to be awards buzz about Frankenstein, I hope it’s for this if nothing else.

Thematically, the film’s structure holds up. The biggest throughline within the film is fatherhood, as one would expect. Victor’s father is a cruel man who thinks himself fair; he married his wife for her dowry and estate and never really thought through what he would do once this was accomplished, other than to attempt to mold his son in his own image through a childhood that is all stick and no carrot. He’s successful, as Victor himself never seems to have given a moment’s thought to what to do with his creation once he bestows it with life, and when his “son” learns slowly, he beats the poor thing just as he was beaten, except with a rage in place of his own father’s placid disappointment. Both sons demonstrate their defiance in exactly the same way, by taking the instrument of “discipline,” Victor taking up the riding crop his father uses while challenging his father to admit to either being fallible or killing his wife, and the creation taking the bar that Victor holds and bending it with his superhuman strength. That’s all well and good, and it works. But what doesn’t are some of the more spectacle-oriented elements. When Victor destroys the tower, there’s a legitimately tense scene of his terrified big baby boy trying to escape, but once he’s out of his chains, it’s all CGI fire and Avatar bodies flying down a 480p chute. It made me think of the “sleigh ride of friendship” that the human lead and the Predator have at the end of Alien vs. Predator (derogatory). Why does it look like this?

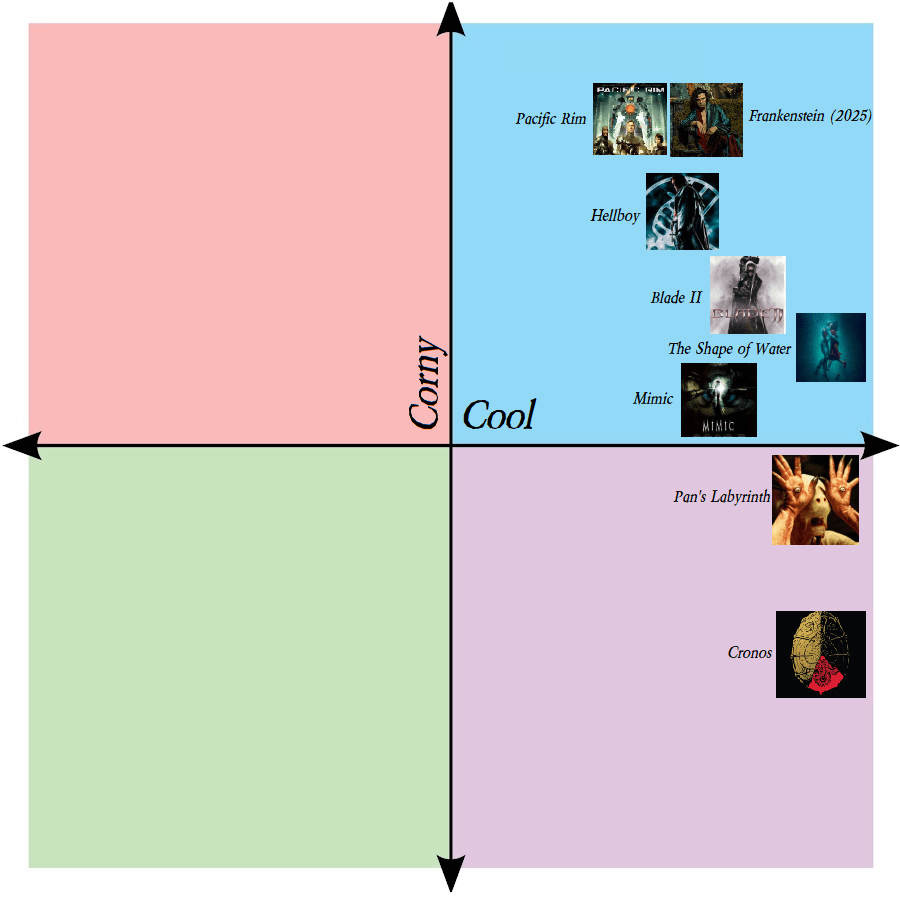

That mixture of corny versus slick is hard to get right. Sometimes, you can get it right in the wrong amounts and make something like Pacific Rim, which gets a mixed response from the general public but becomes an utterly pivotal Defining Work for a subset of diehard fans. Sometimes, you get it right in the right amounts and you get something that’s cheesy but beloved by most, like The Shape of Water. Sometimes you just get it absolutely perfectly right, and Pan’s Labyrinth emerges. Look, I made a (highly subjective and admittedly corny) chart:

This one just didn’t work for me. That doesn’t mean it won’t work for you, though, or that there’s anything wrong with it, objectively. At its length, it might actually function perfectly as a two-part miniseries, split down the middle between Victor and the creature’s stories; it might give you a chance to savor it a little and feel less browbeat by it. It certainly isn’t going to stop me from seeing whichever concoction del Toro mixes next.

-Mark “Boomer” Redmond