-Brandon Ledet

horror

Lisa Frankenstein (2024)

Tim Burton was the very first director I recognized as an auteur, long before I knew the word. Growing up with Beetlejuice, Edward Scissorhands, and Pee-wee’s Big Adventure in constant rotation made Burton’s ghoulish subversion of suburban utopias as easily brand-recognizable as Disney’s white-puff VHS cases. Or so I thought. My developing baby brain would often confuse off-brand titles like Casper, Coneheads, and Addams Family Values for genuine Burton films, something I wouldn’t clear up until I matured enough to pay attention to the credits. Had the new Cole Sprouse zomcom Lisa Frankenstein been released 30 years ago, I’m sure I would’ve confused it for a Burton film as well. The title indicates a mashup of classic creature-feature horror with cutesy late-80s Lisa Frank kitsch, but in practice it mashes up the cutesy-ghoulish sensibilities of opposing suburban auteurs Tim Burton & John Hughes. There’s nothing especially new to be mined from that heavily nostalgic genre blending—especially not in a world where Heathers was around to do that work in real time—but there’s always a fresh batch of developing-baby-brain audiences out there who need their own intro to this stuff, and they could do a lot worse (mainly by watching modern era Burton).

Kathryn Newton steps in to replace Winona Ryder as the starter-pack goth girl inspo protagonist, the titular Lisa. Adjusting to life at a new school with a new family, following the violent death of her mother, Lisa has become a quiet loner with a chip on her shoulder and an aesthetic addiction to black lace. Armed to the fangs with Diablo Cody dialogue, she refers to her peers as “skeezers” & “beer sluts”, while thinking of herself as belonging to a special class of “people with feelings” who listen to college radio. The only person she’ll open herself up to is a Victorian corpse played by Cole Sprouse, whom she initially meets by chatting with his gravestone and eventually resurrects from that grave through a freak, supernatural rainstorm. The walking, grunting corpse becomes a kind of safe boytoy figurine she can confide in and play dress-up with . . . until her self-assigned outsider status gets out of control and the unlikely pair go on a killing spree. They justify the violence by collecting functional body parts for the rotting Creature, but it’s really just an excuse to dispose of the poor souls at the top of Lisa’s personal shit list: her icy stepmother, her handsy would-be date rapist, the bad-boy crush who turns down her own advances, etc. In short, it’s wish-fulfillment fantasy for the angstiest people alive: gothy suburban teens.

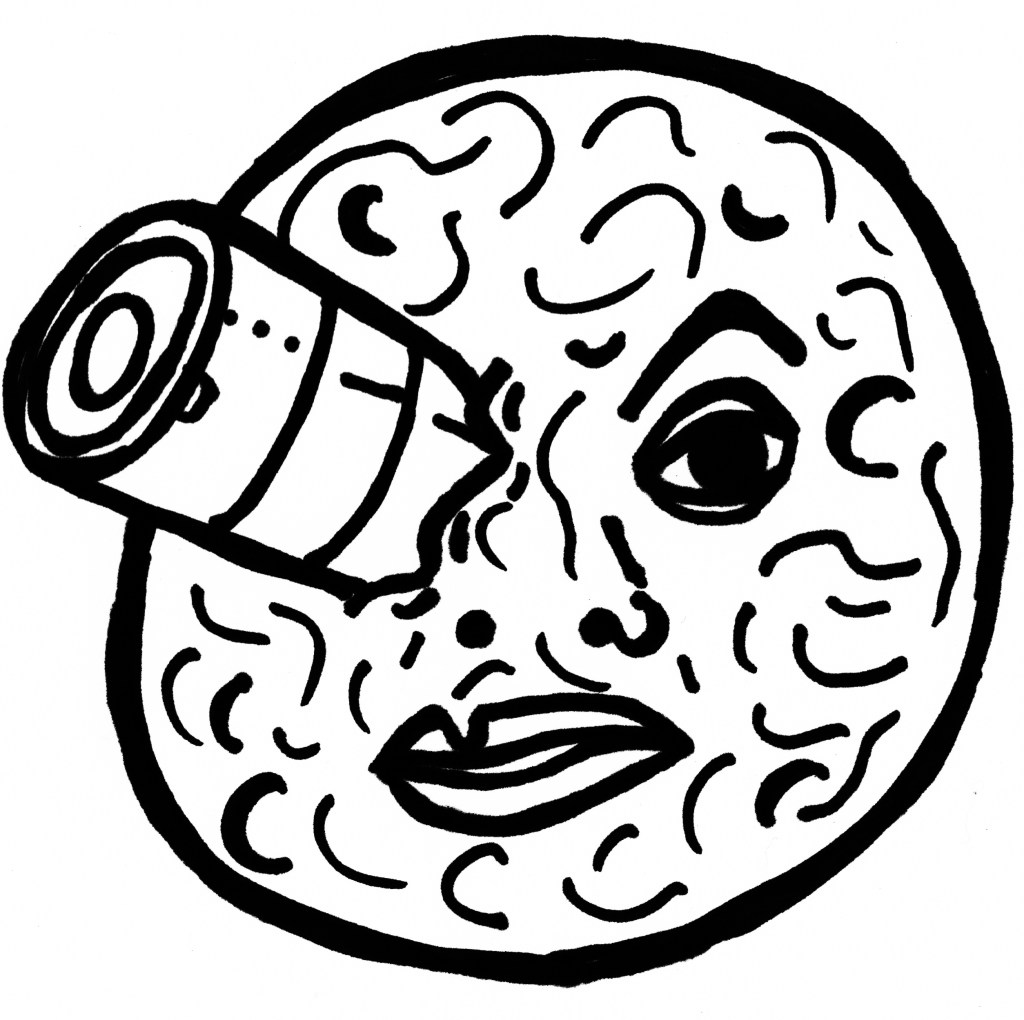

I’m no longer a gothy suburban teen myself, but I like to think I’m still young enough to remember the appeal a movie like this can hold. One of the smartest touches of Cody’s script is the way it allows Lisa to be morally in the wrong, but in a relatable way that recalls the audience’s own lingering teen angst (while also, again, recalling Veronica Sawyer’s). First-time director and promising young nepo-baby Zelda Williams also appeals to an older crowd in her aesthetic nods to Suburban Outsider ephemera from the past, including Burtonized dress-up montages, Smashing Pumpkins-style homages to Georges Méliès, 80s-goth needle drops, and a soul-deep fear of the tanning bed. Unfortunately, though, the movie’s not quite zippy enough to compete with the decades of suburban horror comedies that precede it, from cultural juggernauts like Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands to VHS-era curios like Bob “The Madman” Balaban’s My Boyfriend’s Back. Lisa Frankenstein is thankfully playful enough to avoid becoming the next victim of Age Gap Discourse despite the century’s difference between its romantic leads, which is good news for the teens who haven’t yet seen its dozens of obvious predecessors. It’s just not funny enough to overcome its lax editing & scoring, which allow too many of its zinger punchlines to rot in dead air.

This movie’s undeniably cute, but there’s something missing in it that pushes greatness just out of its reach. Maybe it needed a tighter, zippier edit. Maybe it needed the Danny Elfman touch that made Burton’s early triumphs sing. Or maybe I just needed to be 13 again to fully love it. With my 40s swiftly approaching on the horizon, decades after I’ve needed gateway-horror Burton titles to introduce me to the basic concepts of cinematic style, I’m okay with just liking it.

-Brandon Ledet

Podcast #206: Anguish (1987) & Total Momsters

Welcome to Episode #206 of The Swampflix Podcast. For this episode, Britnee, James, Brandon, and Hanna discuss four cult classics about monstrously mean but lovingly devoted moms, starting with the Zelda Rubinstein horror vehicle Anguish (1987).

00:00 Welcome

03:20 Cat Person (2023)

12:03 Après Vous (2003)

15:28 Breaking the Waves (1996)

20:07 Husbands (1970)

23:59 Soft & Quiet (2023)

29:48 Heavy Petting (1989)

36:04 Anguish (1987)

53:23 Serial Mom (1994)

1:13:00 Mom (1990)

1:24:09 Hush (1998)

You can stay up to date with our podcast through SoundCloud, Spotify, iTunes, TuneIn, or by following the links on this page.

– The Podcast Crew

Fish & Cat (2013)

The great benefit of genre filmmaking is the plug-and-play structure & context it provides artists, the same way poets find readymade structure & context in sonnets or haikus. The deliberately meandering, repetitive Iranian film Fish & Cat would never have found an audience outside its initial festival run without the tropes & traditions of horror cinema illuminating its path. In the abstract, it’s an easy sell as an all-in-one-shot campsite slasher, but in practice it constantly bends space & time to the point where it plays more like experimental theatre than SOV horror. It might have gotten by okay as a slow-cinema critical darling if it were a straight drama about college-age twentysomethings roughing it for the night & flying kites, but a lot of its dramatic tension and, frankly, its marketability would have been lost. Fish & Cat dodges all expectations set by its genre(s), but it also relies on those expectations to lead the audience along like a breadcrumb trail, so that we don’t lose our way in the woods.

The film opens with a Texas Chainsaw-style news item about a rural restaurant that was caught butchering & serving human meat instead of more traditional cattle, way back in the distant, grimy days of 1998. When we meet those cannibal restaurateurs, they’re sizing up a carful of lost, urban college kids who’ve driven down an unmarked dirt road to immediate peril, purposefully giving them confusing directions so they find their way onto the menu. After a tense exchange that notes the “rancid meat” stench wafting from the restaurant, we then follow the two terrifying men into the woods, carrying a mysterious bloody sack, possibly for burial. The horror tropes & tones shift from there when the camera pans over to reveal the cannibal butchers are not alone in the woods, just as they start debating the existence of ghosts. The other figures in the woods are not ghosts, though; they’re college students who’ve arrived to stage an annual kite flying festival (and to be periodically tormented by the elder creeps who occasionally drift into their camp).

Instead of showing off complex camera choreography like most gimmicky single-shotters, Fish & Cat instead uses the format to disorient, often through loopy repetition. Its events do not occur in real time, but instead weave themselves into the near future and near past in a slow, dreamlike rhythm. It’s an approach that allows writer-director Shahram Mokri & cinematographer Mahmoud Kalari to make great use of the woods as a liminal space where anything goes at any time, depending on the momentary, recursive whims of the story. There’s nothing explicitly supernatural about the environment or events surrounding the collegiate kite festival, just as there is no on-screen payoff to the violence teased by the Texas Chainsaw intro. The cosmic déjà vu, precognitive dreams, and impending Armageddon discussed by the characters in casual conversation while they’re waiting for nightfall provide all of the film’s pure-mood scares, backed up by the metal-scraping & inverted music soundtrack cues. Otherwise, all of the implied violence is described in deadpan narration, which switches perspectives as the camera decides to trail a new potential victim every few minutes.

I’d be lying if I said this wasn’t a real patience-tester, especially as home-viewing, but the struggle was very much worth it. There were obvious cultural & political themes that soared over my head in some of the lengthier conversations that break up the scares, but there was enough tension between hopeful youth innocently flying kites while menacing old men lurk around them to infer the sources of tension. I most appreciated the experimental form of its drama, which simulates the “Haven’t I passed this tree before?” feeling of getting lost in the woods, except in this instance the tree is an entire conversation between two strangers. The result is the exact kind of D.I.Y. production that inspires poor, naive teenagers to fall into lifelong debt by enrolling in film school. And maybe those teens would be better served by finding inspiration in its structural use of genre tropes than in the less attainable, communicable merits of the French New Wave, mumblecore, and Dogme 95 festival darlings of the past. If you’re going to impress an audience and pay your rent, you would do well emulating genre titles like Primer, Resolution, Willow Creek, Thou Wast Mild and Lovely, and Fish & Cat.

-Brandon Ledet

Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things (1971)

Usually, when I don’t fully know what to make of a movie, I turn to the Bonus Material footnotes of physical media to search for context. It turns out some movies cannot be helped. The regional horror oddity Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things sets itself up to be the Floridian take on Psycho, but instead delivers a domestic melodrama where everyone’s love language is belligerent screaming. It’s an obvious work of transgression, but also a mystery as to what, exactly, it aims to transgress – recalling other schlock bin headscratchers like Something Weird, The Astrologer, Bat Pussy, and Fleshpot on 42nd Street. Is it a seedy, Honeymoon Killers-style thriller about two sexual degenerates on the run, or a Sirkian melodrama about a gay couple who’ve been shamed by society into fugitive status, one hiding in drag for cover? Who’s to say? All I can report is that David DeCoteau’s commentary track on my outdated DVD copy from Vinegar Syndrome told me more about David DeCoteau than it told me about the movie he was contextualizing.

Sometimes Aunt Martha Does Dreadful Things is like a hagsploitation version of Psycho where Norman Bates never fully gets out of hag drag, stealing a good job away from aging stars like Crawford & Davis. Or maybe it’s more the hippiesploitation version of Psycho where Norman’s personae are split into two separate bodies: a drugged-out free lover who becomes murderously violent whenever he gets in bed with women, and his fellow fugitive sex partner who poses in drag as the hippie’s aunt to avoid neighborhood suspicion of their sordid romance. Aunt Martha claims to despise the Mrs. Doubtfire scenario he’s trapped himself in, but when in private never fully undresses into boymode – often taking obvious, lingering pleasure in the feeling of silk & stockings on his balding, hairy body. When he has to “clean up” the messes (i.e., kill the sexual partners) of his younger, sexually confused lover, the violence only flashes in quick jabs of psychedelic screen-prints & film-negatives. Mostly, we just spend time pondering what’s the deal shared between the two violent, oddly intimate men at the film’s center, a question one-time director Thomas Casey has never satisfyingly answered.

Despite being an expert in the field of low-budget queer transgression himself, David DeCoteau doesn’t have many answers either. He spends most of his commentary-track conversation with Mondo-Digital’s Nathaniel Thompson expressing the same exasperation with what Thomas Casey was going for with this confusing provocation, often sidetracking into rapid-fire lists of other low-budget, transgressive queer ephemera from the 1970s that might help make sense of it in context. It’s a great listen if you’d like to hear about David DeCoteau’s childhood memories about watching The Boys in the Band on TV, or if you’re looking to pad out your Letterboxd watchlist with genre obscurities Sins of Rachel, Widow Blue, and The Name of the Game is Kill. Unfortunately, it also features a lot of DeCoteau complaining that “It’s hard to be politically correct in genre filmmaking” (which is probably true) while casually indulging in some good, old-fashioned transphobic slurs and reminiscing over which trans characters in film have fooled him before their gender situation was revealed vs. which were immediately clockable. In short, it’s a mixed bag, but it says more about DeCoteau than it says about Aunt Martha.

To Vinegar Syndrome’s credit, they’ve since updated that 2015 release with a Blu-ray edition that replaces DeCoteau’s commentary with a new track by Ask Any Buddy‘s Elizabeth Purchell, a trans film historian with extensive knowledge about Floridasploitation schlock. If I get any more curious about how to fully make sense of Aunt Martha, I’ll have to upgrade my copy to hear that alternate perspective. I have no regrets getting to know David DeCoteau better in the version I already own, though, since it’s always been hard to tell exactly how passionate & knowledgeable he is about outsider-art filmmaking in his own work, which can be a little . . . pragmatic, depending on who’s signing the checks. Besides, it might be for the best that I can’t fully make sense of this one-off novelty from a mystery filmmaker. As much as I love the rituals & minor variations of genre filmmaking, it’s probably for the best that not every low-budget provocation can be neatly categorized, or even understood.

-Brandon Ledet

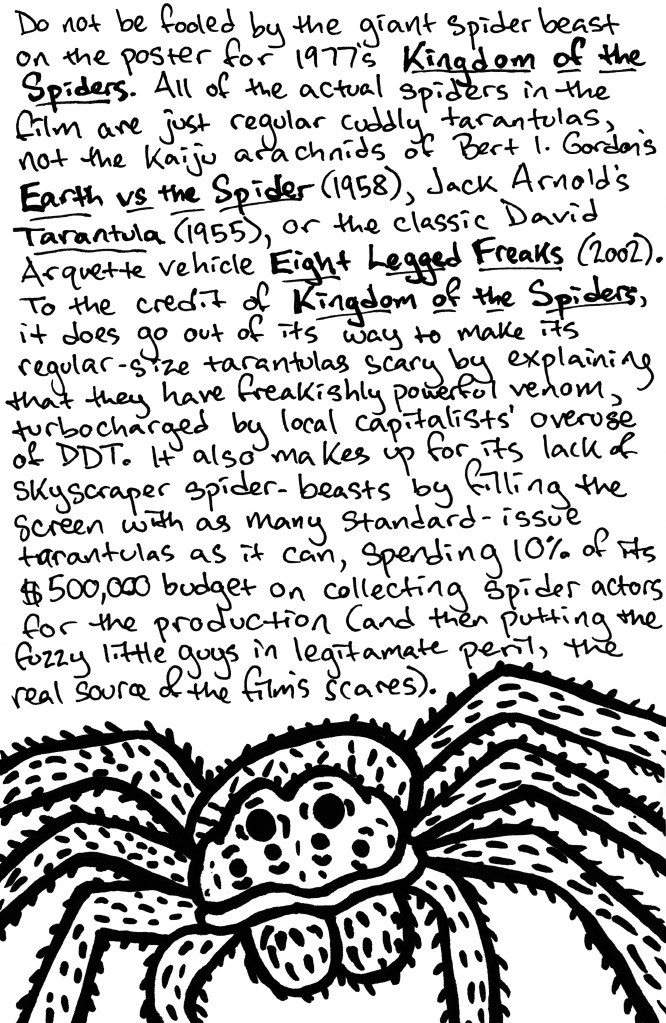

Kingdom of the Spiders (1977)

Destroy All Neighbors (2024)

I have developed parasocial relationships with several of the key collaborators behind the retro splatstick comedy Destroy All Neighbors, which has me rooting for its success. I met one of the film’s writers, Charles Pieper, at a local horror festival a few years ago, and we established one of the most sacred bonds two people can share: social media mutuals. The film’s score was also co-produced by Brett Morris, who produces and co-hosts several podcasts I’ve regularly listened to for over a decade now, which is arguably an even stronger (one-sided) bond. Several of the central performers—including Jonah Ray, Alex Winter, Jon Daly, and Tom Lennon—have all maintained the kind of long-simmering, low-flame cultural longevity on the backburners of the pro media stovetop that also encourages that same kind of parasocial affection, the feeling of rooting for someone to continue to Make It just because knowing of their existence feels like being privy to a deep cut. It seems appropriate, then, that the film is about the kind of long-term, stubborn hustle artists must maintain to complete any creative project in a town like Los Angeles, and how that LA Hustle mindset can also get in those poor souls’ own way. There’s a tricky balance between the lonely self-determination of seeing a project through even though no one else fully believes in it and the simultaneous need to foster collaboration & community to achieve success. The people who made Destroy All Neighbors appear to understand the difficulty of that balance down to their charred bones because they’re all struggling with it in real time; all the audience can do is cheer them on from the sidelines.

Jonah Ray stars as the avatar for that LA Hustle mindset: a prog rock musician who has been tinkering with the inconsequential details of his unfinished magnum opus album for years, with no sign that he’ll ever walk away from the project. Like all frustrated creatives, he blames his creative block on the minor annoyances of anyone within earshot, from the untalented nepo-baby hacks who cash in on their industry connections for easy success to the mentally ill homeless man outside his jobsite who’s just angling for a free croissant. Things escalate when he finally lashes out at one of these annoying distractions from his “work”, a cartoonishly grotesque neighbor with an addiction to wall-shaking EDM (played by Alex Winter under a mountain of prosthetic makeup and a Swedish Chef-style goofball accent). What starts as a neighborly spat quickly snowballs into a full-blown killing spree, and the frustrated musician’s Nice Guy persona is challenged by his weakness for violent white-nerd outbursts. His grip with reality becomes exponentially shaky as his body count rises, and the film slips into a Dead Alive style approach to comic chaos and goopy puppetry, regularly delivering the kinds of practical effects gore gags that earn “special makeup effects” credits in an opening scroll. Does the troubled prog nerd finish his unlistenably complicated rock album before he’s brought to justice for his crimes? It doesn’t really matter. What’s more important is that he learns how to get along with the people around him instead of lashing out while he’s trying to tinker with his art project in peace. It’s just a shame that by the time he figures that out, most of the people around him are reanimated corpses and cops with their guns drawn.

In horror comedy terms, Destroy All Neighbors falls somewhere between the belligerent screaming of a Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 and the nostalgic throwback to old-school splatstick of a Psycho Goreman. If it does anything particularly new within the genre, it’s in its use of cursed guitar lesson YouTube clips instead of cursed camcorder found footage. Jon Daly regularly appears on the prog nerd’s phone as the host of evil YouTube tutorials, filling his brain with poisonous ideas about how if people “get” or “enjoy” your music, you’re automatically a failure and a sellout. He’s just one of many abrasive characters who live in the musician’s head rent-free, though, and to blame the murderous rampage on that one rotten influence would be to misinterpret the film’s overall push for communal art collaboration. Otherwise, Destroy All Neighbors is just impressively gross in a warmly familiar way. It’s playful in its willingness to distract itself from the main narrative just to have some fun with the tools & personnel on hand, exemplifying exactly what the nerd-rage prog boy needs to learn if he’s ever going to finish his magnum opus. What’s amazing is that we’re still rooting for him to pull it off even after the liner notes for his unfinished album now include an “In Memoriam” section. Regardless of whether you’ve ever tried to Make It in LA, anyone who’s ever worked on a noncommercial art project for a nonexistent audience should be able to relate (give or take a couple murder charges, depending on your personal circumstances).

-Brandon Ledet

Lagniappe Podcast: Prince of Darkness (1987)

For this lagniappe episode of The Swampflix Podcast, Boomer, Brandon, and Alli discuss John Carpenter’s Santanicosmic horror Prince of Darkness (1987).

00:00 Plot is Optional

01:56 The Not-So-New 52

11:13 Krampus (2015)

13:39 Muppet Christmas Carol (1992)

17:00 Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005)

19:33 The Holdovers (2023)

22:32 Dream Scenario (2023)

24:09 Suitable Flesh (2023)

26:10 The Boy and the Heron (2023)

31:40 The Royal Hotel (2023)

34:03 Poor Things (2023)

41:45 Stroszek (1977)

46:23 Citizen Kane (1941)

51:52 There Will Be Blood (2007)

53:51 The Seventh Seal (1957)

01:01:11 Christmas Evil (1980)

01:04:52 Shin Kamen Rider (2023)

01:10:12 Time Bomb Y2K (2023)

01:16:28 Crazy Horse (2011)

01:21:34 Peppermint Soda (1977)

01:28:12 The Lathe of Heaven (1980)

01:35:37 Prince of Darkness (1987)

You can stay up to date with our podcast through SoundCloud, Spotify, iTunes, TuneIn, or by following the links on this page.

-The Lagniappe Podcast Crew

Night Swim (2024)

I cannot tell the difference between enjoying a gimmicky horror movie and enjoying getting tipsy to a gimmicky horror movie with my friends. Is the January schlock horror flick about the killer swimming pool genuinely enjoyable, or did I just enjoy hanging out in an empty multiplex on its opening night, opening a couple smuggled cans of sparkling wine to share with pals? Unclear. What I do know is that every calendar year deserves at least one wide-release horror about a killer object, and this year we’re being spoiled with at least two: the one about the killer pool (Night Swim) and an upcoming one about a killer teddy bear (Imaginary). Last year, we were even more spoiled with an especially fun one about a killer doll powered by A.I. (M3GAN). Other recent triumphs include one about a killer dress (In Fabric), a killer jacket (Deerskin), a killer weave (Bad Hair), and the killer pool’s distant cousin the killer water slide (Aquaslash). I’m already looking forward to next year’s Panerasploitation pic about killer lemonade, which could learn a thing or two about how Night Swim stretches a simple premise about killer liquid to fill up a feature runtime. If nothing else, it would make for a fun time-killer on the first Friday of 2025.

If there’s any clear argument against Night Swim’s value as a novelty horror about a haunted object, it’s that it gets distracted from its killer [INSERT NOUN HERE] premise with a second, unrelated noun: baseball. Wyatt Russell continues his campaign to replace Kevin Costner as the go-to Baseball Movie guy by starring as a Major League player whose career is derailed by a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Conveniently enough, his doctors prescribe that he starts water therapy to help lessen the severity of his MS symptoms, an easy win for a man who just bought a house with a haunted swimming pool. In the ideal version of this movie, the pool would be a deadly threat simply because it is a pool, and all action & dialogue would take place either poolside or underwater. In the version we got, the pool is deadly because Wyatt Russell wants to play baseball again, making a bargain with the evil pool to regain the lost functions of his body so he can return to the majors. The pool grants his wish but requires a sacrifice, so Russell has to choose which of his two children he loves less (much like Fritz Von Erich in The Iron Claw). The choice is hilariously easy for Baseball Dad, who has one athletic child and one indoor kid. Still, at some point in the bargaining process he becomes a zombielike soldier who carries out the pool’s evil will even when he’s not swimming – possibly because roughly 60% of his body is made of water, an additional vulnerability on top of his all-consuming obsession with professional baseball.

Distractions on the baseball diamond aside, Night Swim provides plenty of evil swimming pool content for anyone tickled by its premise. It touches on as many pool-related activities as it can in 100 minutes, ranging from the genuinely spooky (reaching into a filter or drain without being able to see what you’re touching, sometimes being greeted with sharp objects or mysterious wet hair) to the deeply silly (horrifying games of Marco Polo, chicken fight, and diving for coins). It cheats on its killer-object premise as often as it can, not only by making Baseball Dad a walking pool zombie but also by filling the pool with the CGI ghosts of past sacrifices. It also shamelessly borrows iconic scares from much better films, referencing both the toy-in-the-drain sequence from IT and the Sunken Place reality break from Get Out. That latter allusion at least feels true to the liminal realms of underwater swimming, though, and Night Swim is at its most convincingly cinematic when the evil pool becomes a boundaryless void disconnected from the baseball-obsessed suburbia above the water’s surface. In one of its most inspired scenes, Kerry Condon (following up her Oscar nominated performance in Banshees of Inisherin with the formidable role of Baseball Dad’s browbeating wife) goes for an ill-advised nigh swim and the camera assumes her POV, revealing demonic jump scares as her head rotates from underwater to sideways surface breaths. It’s a clever gag that can only work in a movie about a killer pool, which is all we’re really looking for in this kind of novelty.

The most potentially divisive aspect of Night Swim is its decision to mostly play its swimming-pool premise with deadpan seriousness. There are a couple moments when it winks at the audience (most notably in a scene where Wyatt Russell explains his miraculous recovery from MS with the inane line “We have a pool”, delivered directly to camera), but for the most part its goofy tone is underplayed. There’s plenty of humor to be found in the fact that every single thought in these non-characters’ heads could be neatly categorized as either “BASEBALL” or “POOL”, but the film thankfully never dives into the self-mocking parody of a Cocaine Bear. The pool is deadly serious business to them, and the inherent silliness of the premise is allowed to speak for itself in contrast to their poolside misery. A lot of audiences will be frustrated by that refusal to indulge in full-tilt horror comedy, but not every first-weekend January schlock release can be a clever crowd-pleaser like M3GAN. It wasn’t Night Swim‘s job to constantly jab the audience in the ribs and ask, “Isn’t this killer pool movie hilarious???” That task is best left to a small group of tipsy friends with a couple hours to kill on a Friday night.

-Brandon Ledet

Podcast #202: Elves (1989) & Santa’s Little Killers

Welcome to Episode #202 of The Swampflix Podcast. For this episode, Brandon is joined by Pete Moran of the We Love to Watch podcast to discuss Christmas horror films about miniature killers, starting with the Yuletide Nazisploitation novelty Elves (1989).

00:00 Welcome

06:53 Little Christmas killers

37:24 Elves (1989)

57:05 Gremlins (1984)

1:17:03 Puppet Master vs Demonic Toys (2004)

1:28:18 The Gingerdead Man (2005)

1:38:03 Krampus (2015)

1:53:23 Toys of Terror (2020)

2:00:06 Silent Night Deadly Night 5: The Toymaker (1991)

2:08:30 Feeders 2: Slay Bells (1998)

You can stay up to date with our podcast through SoundCloud, Spotify, iTunes, TuneIn, or by following the links on this page.

-The Podcast Crew