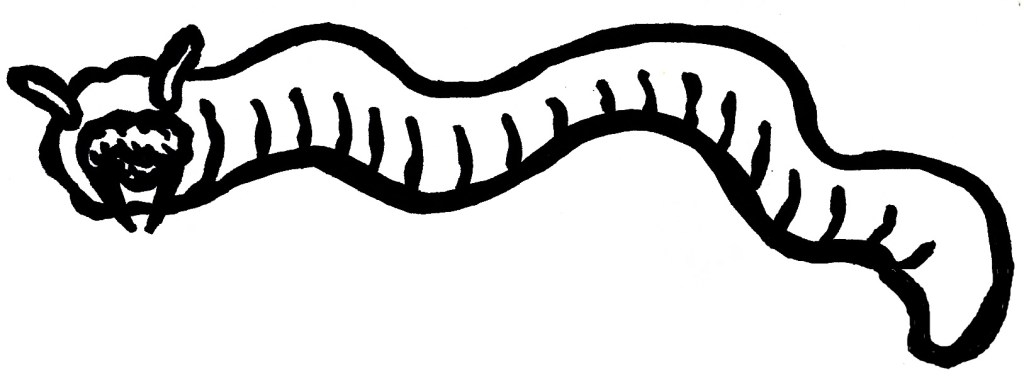

Does sincerity have no place in low-budget genre trash these days? Must all of our D.I.Y. practical-gore freakouts be buried under mile-high layers of ironic detachment and nostalgia for decades of horrors past? I was really hoping the low-budget, psychedelic gore fest All Jacked Up and Full of Worms would live up to the gruesome glory of its title, and in some ways I guess it does. It’s impressively revolting filth in fits & jabs, at least when it’s leaning into the visceral disgust of its wriggling worm imagery – which ranges from real-life worms squirming in cigarette ashtrays to gigantic, intestine-length latex monstrosities stretching across warehouse-scale movie studio voids. It’s too bad all of that effort is undercut by its juvenile edgelord humor, though, as shock value topics like needle drugs, Satanic worship, and pedophilia are frequently mined for cheap, empty punchlines. When you see a “Special Worm Effects By” credit in the opening scroll, you’re prepared for a Screaming Mad George-style descent into Hellish, surrealistic gore. Instead, you get a movie custom made for middle schoolers to prank each other with as a sleepover dare.

Like this year’s much more sincere gross-out horror Swallowed, All Jacked Up is set in a fictional world where consuming worms—either orally or nasally in this case—creates a powerful psychedelic trip akin to an acid overdose. These are just regular, everyday worms, as far as the audience can tell – a conceit that’s underlined by the repetition of the word “worms” in every single line of dialogue. As it’s explained by a worms enthusiast, “There’s only one wrong way to do worms, man […] Not do worms!” This is a pure drug-trip movie, with several loosely connected characters becoming increasingly manic under the worms’ influence. I’d recount their exploits here if they were worth repeating, but they’re mostly just an improv comedy assemblage of self-amused bits that don’t translate outside the troupe. The worm imagery is frequent & remarkably grotesque, but so are the purposeless, off-topic jokes about sexually assaulting babies. Maybe it’s a matter of personal taste (or tastelessness), but I just wonder how much further this movie could push its discomforts if it were a sincere low-budget horror instead of an irony-poisoned horror comedy.

Anyway, if you really want to watch a retro, VHS-warped gross-out that’s overflowing with worms, you might as well watch the 1976 Tubi mainstay Squirm instead. It’s not an especially great film either, but it’s at least a genuine one. All Jacked Up and Full of Worms is a distinctly modern echo of that era’s pure-schlock filmmaking, mimicking long-outdated surface aesthetics instead of seeking genuine, of-the-moment terror. It’s likely unfair of me to pin it under the full weight of modern horror’s weakness for ironic detachment & retro aesthetic worship, but it was also unfair of the movie to make me sit through so many schoolyard jokes about baby rape, so let’s call it even.

-Brandon Ledet