In one of our end-of-the-year podcast episodes last year that was partially inspired by my having finally been convinced to watch The Twentieth Century based on my delight in director Matt Rankin’s follow-up feature Universal Language (it was my favorite movie of last year!), Brandon read off a list of film titles that he asked me to identify as a kind of makeshift quiz. Those titles were all films that had been on the Swampflix Top Ten list for their eligible year, and which I had not seen at the time of the relevant list’s publication. I’m not a completionist, but with an upcoming collaborative project, I took that list as homework and got to work filling out these blind spots to determine if the listed films would have made my own end-of-the-year list if I had seen them in time. Come along with me for part one: 2015-2019.

2015: Boomer’s List vs. Swampflix’s List

Crimson Peak – Watched February 1, 2026

Upon review: Crimson Peak has all of the strengths of Guillermo del Toro’s recent Frankenstein adaptation with none of its weaknesses . . . although it admittedly has other weaknesses of its own, mostly in regards to casting. A gorgeous period film with beautiful costumes and sets that all act in service of a Victorian gothic romance that also happens to be a ghost story, this is del Toro at his best and also his most unabashed. As his main character, an aspiring novelist, says of her own work, “It’s not a ghost story; it’s a love story. The ghosts are metaphors for the past.” The film is almost cringe-inducing in the nakedness with which it comments upon itself, but that same open and unabashed sincerity is what makes it so meaningful and worthwhile. The casting of 2010s Tumblr’s favorite “woobie” it-boy Tom Hiddleston is a miss, and although there’s nothing wrong with Jessica Chastain’s performance, doesn’t it just feel like Eva Green should be playing Lucille? 4.5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Yes.

Tangerine – Watched January 22, 2026

Upon review: I wouldn’t consider myself an Anora hater per se, but I certainly wasn’t enamored of it in the same way that others were. The overwhelmingly positive critical response to a film that I considered solid but not necessarily remarkable made me somewhat hesitant to revisit director Sean Baker’s earlier work, as I felt fairly certain that I would fail to connect with it in the same way that I had with Anora. I was pleasantly shocked by this one, a film that I remember mostly as part of the discourse for the fact that it was shot entirely on smartphones, a brand-new trick at the time. This story of two trans sex workers, Sin-Dee Rella (who recently completed a prison stay on behalf of her pimp/boyfriend Chester) and her best friend Alexandra is an absolutely hilarious, heartbreaking, and overwhelmingly humane piece of narrative cinema. A true slice of life in the day of two women struggling, not to “have it all,” but just to have some little thing, whether it be a sad Christmas Eve singalong that’s barely a step up from a private karaoke room or the pathetic human specimen of Chester (R.I.P., James Ransone). Anora may have had the budget, the big release, and the acclaim, but this earlier outing blows it out of the water. 5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Yes.

2016: Boomer’s List vs. Swampflix’s List

Kubo And The Two Strings – Watched February 6, 2026

Upon review: I was a latecomer to appreciating the animation studio Laika, as I didn’t get around to seeing Coraline, arguably their most famous film, until 2021. I also remember the discourse that surrounded Kubo when it first came out, mostly in the form of criticism of the film’s casting of mostly white voice actors for a story set in and inspired by feudal Japan. While that’s definitely worthy of discussion, I also found Kubo to be an unexpected delight, a gorgeously animated stop-motion film about a boy with magical, musical powers who finds himself thrust into a conflict with his mother’s family following her apparent death, after years of raising the boy in secret. The quest Kubo finds himself upon isn’t the most novel one, but the film takes an interesting twist at the end by having the protagonist forsake the items acquired during his journey and find a more humane way to deal with his evil grandfather. Dark but not too dark, this is one that I would recommend for any child or adult. 4.5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Yes.

Tale Of Tales – Watched January 25, 2026

Upon review: A fantastic fantasy film! When Brandon and I discussed this one while recording our Beast Pageant episode, he mentioned that it had one of the highest hit rates for a horror anthology, and I can’t help but agree. I’ll always think of this one first and foremost as a fantasy/fairy tale picture (it is an adaptation of multiple stories by Italian fairy tale collector Giambattista Basile) before I think of it as a horror film, but don’t be fooled by the Italian poster that makes it look like a collection of episodes of Jim Henson’s The Storyteller; there’s plenty here that aligns more with horror as a genre. A queen (Salma Hayek) eats the massive heart of a giant sea dragon, a dye-maker finds a man who will flay her alive in the misguided belief that it will make her appear younger, a young princess is given to an ogre as a wife and is brutalized by him, and when the last of these escapes, the ogre hunts her down and kills her companions with the ferocity of a slasher. Good stuff. 4 stars.

Would it have made my list? Yes.

2017: Boomer’s List vs. Swampflix’s List

The Lure – Watched January 13, 2026

Upon review: I loved this movie. A bizarre horror musical fantasia, The Lure follows two sirens who are lured onto land by the songs of an eighties Polish pop band called Figs & Dates, then become part of the band’s act before turning into stars of their own. Their eel-like mermaid tales, which only appear when they get wet (Splash or, depending on your generation, H20: Just Add Water rules), don’t prove to be much of an imposition, but when one of the girls starts to fall in love with the Evan Peters-esque moptop bassist of F&D, her more worldly-wise sister tries to get her to break it off. If she doesn’t, she’s in for a Little Mermaid ending, of the Hans Christian Anderson variety, not the Disney one. Running the gamut from club music to pop to thrash, the soundtrack is excellent, and the moments of horror are genuinely chilling. Not to be missed. 5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Yes.

2018: Boomer’s List vs. Swampflix’s List

Cam – Watched some time in 2019.

Upon review: I have to admit that I don’t remember this one too well, although I do recall that I enjoyed it. It’s not possible to legally watch this film anywhere anymore, as it was a direct-to-Netflix feature that the platform no longer hosts and it never got a physical media release, so I don’t have the option to go back and review it again to get a fuller, clearer picture than the one in my head. I remember not caring for actress Madeline Brewer very much at the time, mostly based on her performance on Hemlock Grove; since then, I’ve come around on her, especially when I came to like her quite a bit as the protagonist of the final season of You. This was one that hit with a lot of the Swampflix group based on the predisposition toward internet-based horror, and it went over fairly well in my house with me and my roommate of the time. Too bad I can’t confirm that anymore. 4 stars.

Would it have made my list? 2018 had some clear leaders of the pack with Hereditary, Annihilation, and Black Panther, but the lower rankings on the list aren’t as solidly defensible. Verdict: Possibly, lean toward yes.

Mandy – Watched January 29, 2026

Upon review: Back when we watched Beyond the Black Rainbow as a Movie of the Month years back, I remember reading that as a child director Panos Cosmatos would walk down the horror aisle at the video store and imagine what a movie would be based on the poster alone. Looking back on that, I do wonder if the abyss didn’t gaze back a little, since he has a tendency to make movies that sometimes linger on a single image for extended periods of time, as if the film is the poster. That bothered me much less in Mandy than it did in Rainbow, possibly because it’s driven by yet another in a long history of butterfly fearless performances from Nicolas Cage, or because this one’s nostalgia for VHS-era horror is more textual than referential. The evil gang of demonic bikers who help a cult subdue and torment the titular Mandy are almost exactly what one might imagine from sneaking a peak at the horror aisle at age eight and seeing the cover of Hellbound: Hellraiser II while an overhead TV played Psychomania. The psychedelia and too-familiar narrative structure are unlikely to please plot essentialists, but as a chainsaw duel enthusiast and a King Crimson fan, I liked this despite the soporific nature of its back half. 4.5 stars.

Would it have made my list? I think that I would have overlooked this one or taken it for granted during the year of its release, especially given my cool reception to Black Rainbow. So no, it would not have made my list, but that would have been an error on my part.

Eighth Grade – Watched February 6, 2026

Upon Review: Most online sources would say that this is a coming-of-age dramedy, but that would be incorrect; this is a horror film. Our young protagonist Kayla (Elsie Fisher) is growing up during a time in which social media use is essentially compulsory, while she’s also trying to navigate a world that, to the adult viewer, is largely alien, all while her hormones surge amidst a peer group whose treatment of her ranges from cruel to apathetic. That strangeness of the world in which children reside “now” (given that the film itself is nearly a decade old at this point) is made manifest in a scene during which Kayla spends some time with an older girl and her high school friend group, all of whom seem infinitely older and wiser to Kayla than herself despite the fact that they themselves are still children (and not that their youth stops one of them from being a predator). These older teens marvel at the idea that Kayla had SnapChat, a messaging app that their contemporaries use almost solely for exchanging nudes, when she was in fifth grade, and it blows their minds in the same way that I often marvel that there are entire generations now that have grown up on YouTube, a site that launched the summer after I graduated from high school. Kayla’s entire life is inscribed by the age-old pubescent need to be seen and acknowledged, filtered through a world in which validation is a currency that exists entirely within one’s phone. Good stuff. 4 stars.

Would it have made my list? Yes.

In Fabric – Watched April 4, 2025

Upon Review: An absolute marvel of a movie, I just happened to miss this one when it appeared, despite the affection I already held for Peter Strickland’s earlier giallo-adjacent psychological thriller Berberian Sound Studio. Featuring an excellent turn from Marianne Jean-Baptiste, one of our greatest living performers, this spooky feature about a red dress that torments its owners is an absolute delight. Briefly discussed at the time of viewing in our Buddha’s Palm episode at about the seventy-two minute mark. 4.5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Absolutely.

The Wild Boys – Watched December 21 and 22, 2025

Upon Review: I was not looking forward to disappointing Brandon when I watched this one and did not care for it. So much so, in fact, that I watched it again the following day to see if there was something that I could connect with and care for. Unfortunately, this proved not to be the case. A mostly monochrome fantasia about boys becoming women on an island full of erotic flora, I felt in my bones how strongly this would connect to Brandon, but it just didn’t with me. The moments I loved most were when the film would suddenly turn almost Technicolor, bright and vibrant, and then would be disappointed when we went back to black and white. There must have been a reason for not shooting the whole thing in glorious color, but I couldn’t pin down exactly what the reasons were despite two viewings. It is, as Brandon wrote in his review, “decidedly not-for-everyone-but-definitely-for-someone.” 2.5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Alas, no.

2019: Boomer’s List vs. Swampflix’s List

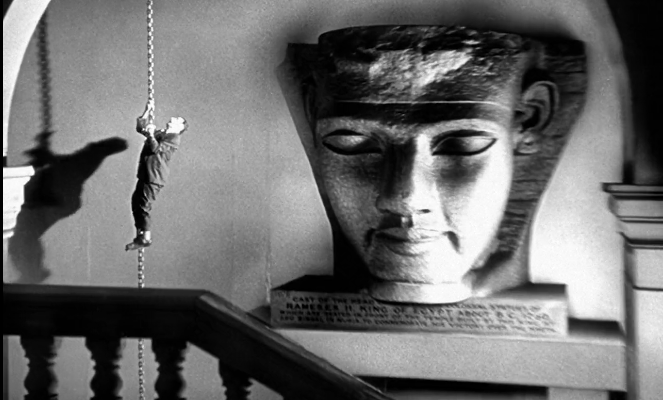

The Lighthouse – Watched January 11, 2026

Upon Review: I was a big fan of The VVitch, so much so that it was my number one movie of 2016. Despite that, I let both of director Robert Eggers’s following films, The Lighthouse and The Northman, slip past me in the stream. Perhaps it was simply a matter of not being up to grappling with the film and its presaging of the madness of isolation when the film came to home viewing in the early days of lockdown. Having now seen The Lighthouse, this was a huge miss on my part. An utterly captivating story about two men on an island together tasked with maintaining an apparatus that captivates them like it were an unknowable elder god, the film is as rich with symbolism as it is dense with the old-timey dialogue for which Eggers continues to demonstrate his uncanny ear. An unpleasant delight. 4.5 stars.

Would it have made my list? Absolutely; it would have hit the top 10.

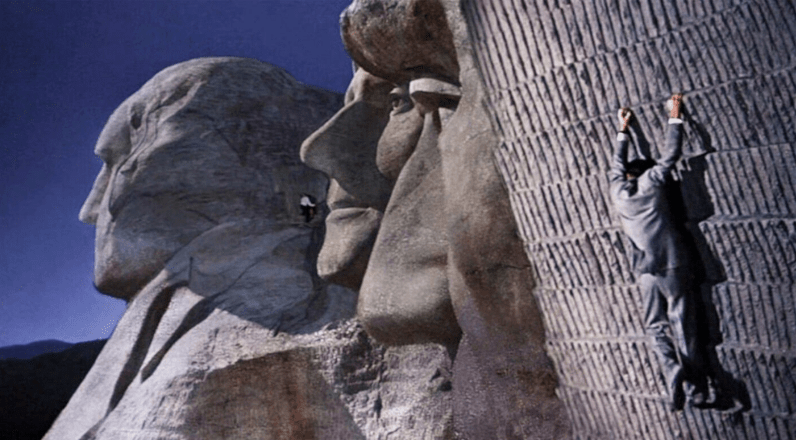

The Beach Bum – Watched January 20, 2026

Upon Review: Matthew McConaughey plays the worst person in the world, a very famous (Florida specific) poet named “Moondog,” who floats through life on little more than military grade marijuana, beer that’s barely fit for swine, and a garden of sun-dried poontang. This life of luxury is not sustained by his poetry, but by the fortune of his wife Minnie, who loves no man but Moondog but has taken to shacking up with R&B artist Lingerie (Snoop Dogg) in the “civilization” of Miami during Moondog’s long hiatus in the Keys. When Minnie tragically dies, the plot, such as it is, kicks in, as Moondog must now finish his current writing project in order to get the inheritance that will continue to fund his degenerate hedonism. Along the way, McConaughey as Moondog gets to spout the occasional fragment of genuinely decent poetry broken up with narcissistic phallocentric drivel that believably charms whatever constitutes the literati of Jacksonville and, less convincingly, the Pulitzer board. It’s all good fun with great editing, delirious neon, and a practiced eye for composition, but I could see this turning into a red flag favorite long term in the same genus as Fight Club or Scarface. 4 stars.

Would it have made my list? Not this time.

-Mark “Boomer” Redmond