Every month one of us makes the rest of the crew watch a movie they’ve never seen before & we discuss it afterwards. This month Erin made Boomer, Brandon, and Britnee watch Mrs. Winterbourne (1996).

Erin: Picture it: 1996. Clothes are big, scrunchies are bigger, and a Hollywood team looked at the script for Mrs. Winterbourne and decided that this was the perfect vehicle to launch Ricki Lake into Leading Lady-hood.

The same Hollywood team also thought that the best way to adapt a gritty noir novel about a pregnant woman escaping domestic abuse in the midst of a deadly train wreck and a grieving family was as a lighthearted romcom.

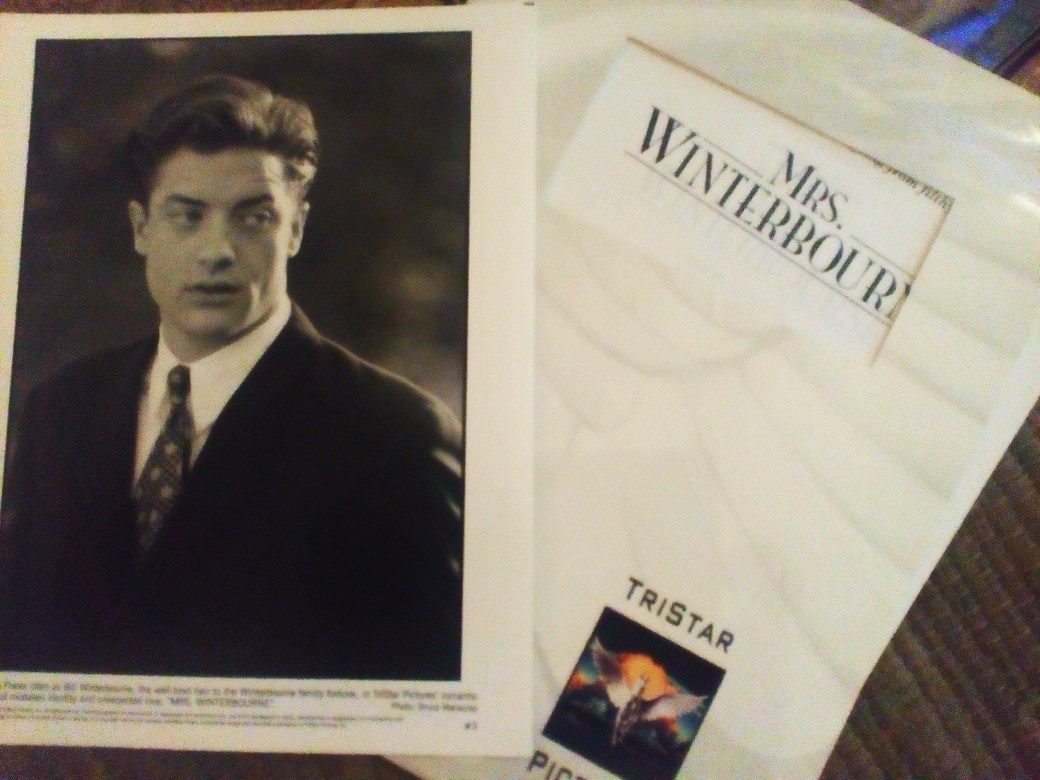

That’s right. Mrs. Winterbourne is a romantic comedy about a pregnant teenager (Connie, played by Ricki Lake) escaping her scummy, abusive boyfriend, surviving a train wreck that kills another pregnant woman and her kind husband, and being mistakenly taken in by the in-laws (Shirley MacLaine and Bredan Fraser as mother- and brother-in-law) of the dead woman as they attempt to put their hearts back together. That’s only the first act. In the second act, just as Connie is starting to connect to the Winterbournes and is struggling with the decision of either revealing her true identity or keeping up the charade indefinitely, her slimy ex-boyfriend comes back to blackmail her. There’s singing! Dancing! A makeover montage! Murder!

Although I really enjoy Mrs. Winterbourne, the incongruity between the gritty (and bizarre) premise and the lighthearted style in which it is presented makes for a weird movie-watching experience. There’s a lot of whiplash as the film attempts tell a gritty noir story through the lens of a quirky romcom.

The supporting cast does several things rather well – Shirley MacLaine as the elder Mrs. Winterbourne might be the true heart of the film, and there is real chemistry between her and Lake’s Connie and Fraser’s Bill. Miguel Sandoval, as the Cuban ex-pat chauffeur, is truly charming as he slings knowing glances and come-to-Jesus talks left and right. Loren Dean brings a completely awful character to life in Steve DeCunzo, throwing change at a pregnant Connie through his window as she begs for help in pouring rain and stomping around in the baby’s playpen as he threatens blackmail.

Honestly, the least believable thing for me in this movie is the lack of chemistry between Lake and Fraser. Brendan Fraser had hit his stride in the mid ‘90s, playing hot and goofy leading men after a few years of playing stoner and college roles. He still had George of the Jungle (1997), Gods and Monsters (1998), and The Mummy (1999) to come. Ricki Lake, while she never really hit leading lady status outside of Mrs. Winterbourne, was a ‘90s fixture, and would start her talk show in 1998. Despite being in their respective zones in 1996, they just don’t really connect, which is a shame.

Over all, I think that Mrs. Winterbourne is a fun watch. It’s good natured about its downer plot line, and has a few really funny and touching moments. I like strange movies, and this one is definitely strange enough to keep my attention.

Brandon, Mrs. Winterbourne is pretty wacky. What are your first impressions of it? How does well does the romcom genre flesh out the noir bones? What caught your attention about Mrs. Winterbourne?

Brandon: Yeah it’s difficult to write my first impressions on this film without zeroing in on the fact that it’s a fish-out-of-water romcom with a “hilarious” comedic set-up that’s put into motion by a pregnant woman dying in a train wreck. The film’s moody vibe as a neo-noir is in direct conflict with its more lighthearted comedy stylings: a pregnant & homeless Ricki Lake wandering aimlessly in the rain, a butler who escaped homophobic persecution in Cuba through prostitution, a third act murder mystery, the fact that Brendan Fraser’s cad finds himself falling in love with a woman who might be his dead twin’s widow. So much of Mrs. Winterbourne is so darkly fucked up that it’s jarring to watch the film wrap itself in the soft-edge confines of the romcom genre. My favorite moment where these two tones clash is when Ricki Lake’s pregnant/homeless Jersey Girl shouts to her deadbeat baby daddy “I’m about to have your baby out on the street! Wanna come watch?” Uncaring, he tosses a quarter at her feet & shuts his window. Later the baby daddy’s new baby mama recognizes Lake’s protagonist only as “The Bitch Out in the Rain With the Quarter.” I shouldn’t have gotten such a hearty laugh out of that but I shrieked with delight. What a messed up “gag”.

The weirdest part about the film’s compromised tone is how much weight it puts on Ricki Lake’s shoulders. She’s asked to deliver most of the film’s yuck-it-up comedy, which I’d say she accomplishes with just as much bright eyed enthusiasm she brings to John Waters’ (utterly flawless) Serial Mom. At the same time, I’d say that the sole reason the film’s central romance plays like a joke is the very same Ricki Lake performance. Brendan Fraser is entirely believable as the romcom heartthrob, but Lake is too much of a bumbling fool for me to genuinely commit to her end of the romance angle. Maybe it’s all those years of watching her host a Jerry Springer-style talk show that keep me from forgetting the clownish aspects of her screen presence, but I think her making homelessness amusing was an asset, but her making romance funny might’ve been somewhat of a detriment.

Where do you fall on Lake’s performance, Boomer? Is she a sold lead in this role or did the film ask too much of her in too many directions for the performance to be taken seriously?

Boomer: I have a confession to make; I used to hate Ricki Lake. This was through no fault of her own and was based entirely on Baton Rouge NBC affiliate WVLA’s decision in 1997 to replace their daily 4 PM rerun of Star Trek: The Next Generation with her syndicated talk show. In the many years since this great sin was committed, I’ve actually come to like Lake quite a bit, especially as I came to be aware of her partnerships with John Waters in my teenage years. She’s a perfectly serviceable actress, and she’s genuinely likable in this role, which could so easily have not been the case with a plot like this that revolves around deception (although Connie does admirably make every effort to correct misconceptions up to the point where revealing the truth could potentially literally kill a woman). Her weakest acting moments come in the scenes in which she is called upon to be histrionic and melodramatic that she comes across more like one of the sideshow people who populated her television stage. Lake can act; she just can’t overact, and she works best when she’s playing off of MacLaine, who brings a warmth to her performance that Lake can’t help but reflect back at her.

The weakest acting link, frankly, is Fraser, who comes across as a bit of a hack here. He seems to think that “playing rich” requires foppishness that borders on recreating stereotypical portrayals of gay men, up to and including the fey and effete way that he drops his napkin in his lap in affected shock at Connie’s initial appearance at the dinner table. There are many other ways to play a man of privilege who assumes that the new family member in his midst is an interloper, but Fraser read his part and went straight to “dandiest dandy that ever dandied,” and the later scenes that show him as a man with the potential to be more open doesn’t erase his performance in his introduction. In fact, when he first started falling for Connie, my assumption was that the film was leading into his public confession that he had latched onto her in an attempt to disprove his homosexual leanings. But no, it was just that Fraser made poor character choices when filming the earlier sequences in the film, and, admittedly, I came around on his character by the end, even if he is stiff and wooden when confronting Connie about having (he assumes) killed Steve.

The standout performance was MacLaine’s, and I especially liked how I expected the plot to unfold in the opposite direction that it does (i.e., that the rich patrician mother would be slow to warm to the new bride her son took an instant liking to, rather than the other way around). This twist helps the film feel less stale than it otherwise could. What do you think, Britnee? Did MacLaine help make this movie “work” for you, or no?

Britnee: MacLaine’s performance was nothing short of perfection. Every line she spoke and move she made was so effortless. I just couldn’t take my eyes off her! However, she officially stole my heart when she hid a lit cigarette in her mouth. It’s definitely not the kind of behavior one would expect from an elderly socialite, and that’s the kind of shock value that I live for.

When I think of how the film would be if there was no MacLaine, I have to say that I still would have enjoyed it. Of course, it wouldn’t be as pleasurable without her, but it would still be a great film. As a fan of Ricki Lake, I can’t help but feel as though she was the one who stole the show. She brings this sort of ridiculous yet unique style of humor to every film I’ve ever seen her in, and this is especially true with Mrs. Winterbourne. Lake as Connie Doyle was beyond entertaining. She does a good bit of overacting throughout the film, especially when she bring her Jersey Girl sass to the upper-class society of Boston. While overacting is usually viewed as a acting flaw, it’s a huge part of Lake’s comedic style, and it always brings out tons of laughs from me.

It’s interesting how this film and our previous movie of the month, Big Business, share the “poor girl in a rich world” theme. Erin, what are your thoughts on this similarity? Does this theme work better with Mrs. Winterbourne’s style of comedy as opposed to Big Business?

Erin: You know, Britnee, it didn’t occur to me that Mrs. Winterbourne and Big Business are similar in their fish-out-water, mistaken identity plots. Now that we’re looking at similarities, I think the over all feel of these movies has something else in common – while Big Business feels like an Old Hollywood screwball comedy, Mrs. Winterbourne is based on a 1948 noir novel. I think that the old camp melodrama present in both movies gives them a feeling of a previous era in which audiences might have had more forgiveness for such silly premises.

I’m not sure if either movie works “better” with the “poor girl in a rich world” theme. Big Business is a madcap comedy, and hardly touches the ground at all. It’s a hysterical rush through a farcical plot. Mrs. Winterbourne attempts to have some soul or grounding in drama, but all in all seems to have trouble straddling the line. Both movies take that particular plot point, as well as the mistaken identities and old school feel, to push different stories along.

I think that one of the biggest differences between Mrs. Winterbourne and Big Business is something that I only noticed in this viewing. Big Business holds its main characters as intrinsically subjective within the world of the movies. The movie starts with something beyond their control, the baby swap, but then only advances with actions of the characters. The Sadies and the Roses are shown, despite their immersion in a comically out of hand situation, to make the world of their movie theirs. Connie, despite being the main character of Mrs. Winterbourne, is almost completely an object in her own world. She decides to leave her father’s house in the first minutes of the movie, and then everything else happens to her. Her attempts to take actions are either preempted by other characters or she is talked or coerced out of decisions.

I’m not sure how to understand or interpret this lack of subjectivity in the main character. Brandon, what do you think? Any thoughts on why Connie is so objective in her own story, and what that means for Mrs. Winterbourne?

Brandon: If you’re looking to further solidify Mrs. Winterbourne‘s connection with Big Business, consider that they not only both deal in mistaken identities & fish out of water humor. Their plots also revolve around sets of estranged twins, which is kind of an obscure angle for a comedy. Ricki Lake’s protagonist has no twin in this film, though, which is unfortunate, as it would’ve been fun to see her match the eccentricity of the rest of the cast. She also doesn’t, as Erin points out, ever really enact the changes in her life that transform her from homeless Jersey Girl to wealthy heiress. The film’s events just sort of swirl around her as if her rightful place among the affluent was simply a matter of fate.

I think the passive aspects of Connie’s personality transforms parts of Mrs Winterbourne from a silly romantic comedy to a kind of a fairy tale. And I mean fairy tale in the sense of fantasy wish fulfillment more so than Brothers Grimm. Connie never really learns any lessons or grows as a person throughout the film. She mostly just allows the world to pave the way for her road to happiness in which Brendan Fraser is the closest thing to a prince a modern girl could wish for & a milquetoast life surrounded by immense wealth is the height of happily ever after. Keeping Connie passive & grounded leaves open a hopeful It Could Happen to You interpretation for the audience at home, which is not far from the kind of escapism romcoms aim to sell in general. The details that make this fairy tale angle in Mrs Winterbourne feel tonally bizarre, though, are the film’s darker plot points: a miscarriage, a train wreck, a murder. It seems that, according to the film, happily ever after often comes with a body count on its price tag.

What do you think, Boomer? Is Connnie’s passiveness an intentional choice that allows the viewer to step into her shoes & live out her (somewhat deadly) fairy tale or did the writers merely fail to consider giving their protagonist a sense of agency?

Boomer: I’m glad that Erin brought up the original novel above, because I was shocked to learn when viewing Winterbourne‘s Wikipedia page that it was adapted from a Cornell Woolrich novel. I went through a noir phase in my teens and although I never read the novel from which this film drew inspiration, I did read some of his other works, and this movie is quite dissonant tonally. I recently reviewed the Francois Truffaut film The Bride Wore Black, which was also adapted from a Woolrich novel of the same name, and that film is much more in line with the Woolrich vision. As counterparts to each other, Bride and Winterbourne couldn’t be more dissimilar, because Brandon is right; this flick is essentially a fairy tale of wish fulfillment.

Connie doesn’t exhibit much in the way of agency in any of the directions that her life takes. This makes sense if you think of her as a rags-to-riches fairy tale girl. Cinderella doesn’t do much but have decisions made for her and be lucky enough to have a magical godmother; Rapunzel is stuck away in a tower until the plot finds her; Talia is comatose in a castle until her “hero” comes along. Connie is much the same; she gets conned, kicked out into the street, pushed onto a train that she doesn’t intend to board, and wakes up after it crashes wearing a dead woman’s nightgown and life. The film is smart to counterpose the agency-free Connie with Grace (and even give them both names that are virtues, as we learn “Connie” is short for “Constance” in the final scene). Although Paco and Bill pester her about taking her medication and not drinking or smoking, it’s evident that Grace runs the Winterbourne household. We would normally see a woman like Connie, who is moved about like a chess piece by other people, used to prop up the story of her love interest. Instead, her more static narrative is used to expand Grace’s dynamic story. In a lot of ways, the film ends up being more of a love story between Grace and Connie than Connie and Bill.

The film is also smart to allow Connie time to make multiple attempts to tell others that they have mistaken her for somebody else only to be ignored, and she still considers it up to the point where she realizes that the truth could literally kill the elder Mrs. Winterbourne. It helps keep the audience’s sympathy with Connie instead of against her. I know you said above that you feel Lake’s broader approach to the material helps it play as funnier than it would otherwise. Imagine that Lake was not available; who would you cast in her part, and why? If you could recast one other person, who and why?

Britnee: Ideally, I would love to see a young Barbra Streisand play the role of Connie. Not only is she my favorite “funny lady,” but she knows how to pull off a romcom, which, as much as I adore her, Lake just can’t seem to accomplish. Unfortunately, Streisand would be more suited for the role of Ms. Winterbourne during the time of the film’s release, so this an impractical choice. Being a little more realistic, I would without a doubt cast Natasha Lyonne for the role of Connie. I can’t help but think of how perfect she was as Vivian in Slums of Beverly Hills, and I see a lot of Vivian in Connie. Two sassy, street smart ladies trying to make their way in this big, cruel world.

If I was given the choice to recast another person, it would definitely be Brendan Fraser. He was just so bland and almost robotic. I understand that his character (Bill) is supposed to come off that way for the most part, but when Connie becomes his love interest and he goes through his little personality change, it just doesn’t feel natural. However, I do have to say that he was excellent in George of the Jungle and Airheads, but I’m not sure if that’s necessarily a good thing. When it comes to recasting Bill, I would chose James Spader because he is perfect for that type of role. He’s great at being a total snob (Pretty in Pink), but he’s even better at being a romantic snob (White Castle). Spader and Lyonne would have been such an iconic romcom couple.

Lagniappe

Erin: It’s a shame that Brendan Fraser and Ricki Lake have such little genuine chemistry. The plot is already pretty forced, and some real passion between Fraser’s Bill and Lake’s Connie would have given an ounce or two of believability to a storyline that requires a man to fall in love with his twin brother’s widow.

Britnee: Connie’s little “makeover” was so unnecessary. I could understand the need for a makeover scene if she had ratty hair and holes in her clothes, but her hair was gorgeous and her outfits were so on point. All they did was give her shorter hair and a couple of new tops. Lame!

Brandon: One of the more absurdly funny aspects of Mrs. Winterbourne was how undercooked Connie’s baby looked in the film. I’m not sure if they cast an infant that was too young for that kind of physical labor or what, but the way Connie’s child was always helplessly thrusting its little arms in the air as a wide range of actors jostled & played with it was so dangerous looking in a way that made me laugh fairly consistently (through my heartfelt concern, of course) whenever it was being passed around. I’d like to check back in with the now-20 year old Mrs. Winterbourne Baby in 2016 to see how their neck & limbs are doing, because I could swear the camera caught some permanent damage somewhere in there.

Boomer: I didn’t expect that the truth would be revealed by the appearance of Connie’s ex; I was looking for the late Mrs. Hugh Winterbourne’s family to look up their daughter and discover Connie living her life. Given that this never happens, I can’t help but wonder what will occur when they come to visit their grandchild. Further, considering that all their problems were resolved by a stranger murdering the loose ends, I hope they just send letters. It’s bad luck to interfere with the Winterbourne family destiny, apparently.

Upcoming Movies of the Month

March: Boomer presents My Demon Lover (1987)

April: Brandon presents Girl Walk//All Day (2011)

May: Britnee presents Alligator (1980)

-The Swampflix Crew