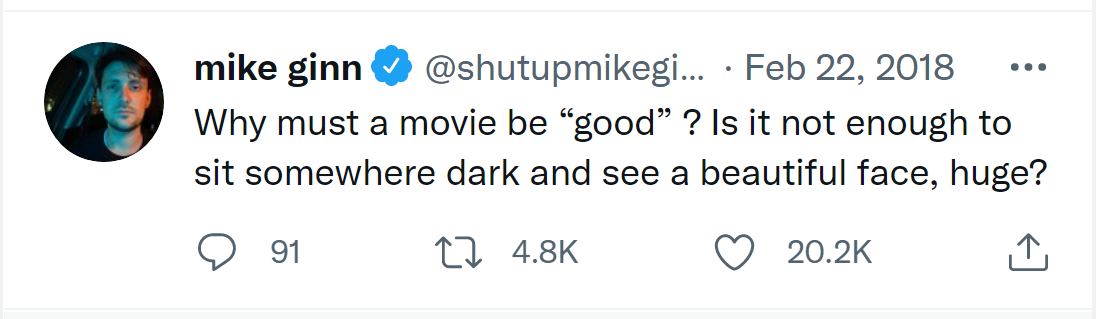

About every 1.6 weeks, someone gets on Twitter and asks some variation of “What’s the best tweet of all time?” There is always of course, the trotting out of the greats, like this one, this one, this classic, this jab, this burn, this zing, mockery of the New York Post, a personal favorite, someone who presumed the universality of a ludicrous idiosyncratic belief and chooses to dickishly ignore that they’re completely wrong, and of course, the truly greatest tweet of all time (and these two, which go out to my friends back home). But what’s “best” anyway? For me, all of these pale in comparison to this tweet, which I think about at least once a week:

It came to mind again most recently yesterday, as I sat in a movie theater for the first time since Emma., watching Scarlett Johansson and Florence Pugh engage in a car/motorcycle/tank chase through the streets of Budapest and into the city’s subway, exchanging quippy dialogue all the while. In that moment, I flashed back to the similar car chase sequences in Berlin in Civil War, Seoul in Black Panther, San Francisco in Ant-Man and the Wasp, and [Cleveland as D.C.] in Winter Soldier, as well as probably others that I’m forgetting. And although this was another movie that largely stuck to the tried-and-true Marvel formula, I thought to myself, Why must a movie be “novel’? Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a thrilling car chase through a metropolitan area, huge? After all, although this isn’t the first MCU film all about one of our lady heroes, it’s leaps and bounds better than Captain Marvel, which I gave a high star rating to upon release but was largely tepid about it in the review proper (I literally wrote “I’m hot and cold on this one”) and which I look back on now mostly with contempt, as its imperial Yvan eht Nioj underpinnings have only become clearer with the passing of time.

I’ll admit here that, by and large, it’s pretty easy for a film to manipulate me emotionally (the people would like to enter into evidence my likewise high star rating for 2016’s Ghostbusters), and it’s also not just films that do it. The Alamo Drafthouse has, for the past few years, used the same simple animated introduction before new releases where several colored circles appear, then overlap, then space out to mimic planets orbiting a star, then come back together to embody the six circular cut-outs of the classic film reel canister. My description is overselling the complexity, I think, but I can’t find it online anywhere so forgive me. The sound design of it is fairly simple as well, but this time, after the theater darkened and the traditional Alamo font appeared on screen saying “We missed you,” the pre-show included a montage of clips of characters from the movies at the movies: Amélie, Taxi Driver, Cinema Paradiso, etc., and then the bonging tones of that intro came together, and I was overcome. It felt like coming home, and if I’m warmer to Black Widow than it truly deserves because of it, well, maybe the people will have to enter this review into evidence one day, too, but for now, I have to say, I really liked it. Even my best friend, who is generally apathetic to Marvel movies, thoroughly enjoyed it; immediately afterward, she said she would be willing to pay to see it again, and when we were considering watching another movie back home last night, she said she’d rather just watch television than another movie because she enjoyed Black Widow so thoroughly that she wanted to “marinate” in it a while before another cinematic experience watered it down. Take from that what you will.

We open in Ohio in 1995, where a young Natasha (Ever Anderson, daughter of Milla Jovovich and Paul W. S. Anderson) rides her bike through suburban streets and into her backyard, where she plays with her younger sister, Yelena (Violet McGraw). When Yelena skins her knee, their mother Melina (Rachel Weisz) attends to her, and there appears to be some tension between Natasha and dear old mom. As night falls, Yelena notes the appearance of fireflies in their backyard, and Melina gives her daughters a little science lesson about bioluminescence. While they set the table, father Alexei (David Harbour) returns home, agitated. He shows Melina a 3.5’’ floppy and notes that “it” is “finally happening.” As Melina whispers a meaningful apology to Natasha at the dinner table, Alexei grabs a rifle and the entire family hops into their SUV and makes haste toward a small airstrip, with S.H.I.E.L.D. agents in pursuit shortly. After a tense shootout, the family manages to make their getaway in a prop plane and land in Cuba, where we learn that the “family” is comprised entirely of Russian agents, even the two children, and that the past three years in America have been part of a long term operation at a secret S.H.I.E.L.D. facility. Natasha attempts to prevent her separation from Yelena, citing that the younger girl is only six years old and too young for training, but Alexei notes that Natasha herself was even younger when she first began, and the two of them are forced apart on the orders of General Dreykov (Ray Winstone).

After an opening montage (set to a downbeat cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit”) gives us the general impression of what constitutes a Black Widow’s training in the “Red Room” (it’s not fun!) we move forward to 2016. The rest of the film is set parallel to the events of the aforementioned Captain America: Civil War, following Natasha (Johansson) in hiding after siding with Cap against Tony re: The Sokovia Accords. Elsewhere, Yelena (Pugh) and a team of fellow Black Widows tracks down and ultimately kills a rogue Widow, but not before her former ally exposes her to a red dust that acts as a counteragent to Yelena’s Black Widow programming, which we learn has grown beyond conditioning and brutal training to literal mind control. Natasha makes her way to a safe house in Norway with help from her friend Mason (O-T Fagbenle), who also delivers some things left behind at her last safe house in Budapest, which includes a package from Yelena that contains several vials of the red dust; the dust, in turn ends up drawing the attention of Taskmaster, Dreykov’s right hand killer, who has the ability to mimic the fighting styles of anyone from merely watching a video. Yelena and Natasha reunite and decide to destroy the Red Room once and for all. In order to do so, they must first rescue their “father” from the Siberian gulag to which he has been sent; the former “Red Guardian,” the only successful supersoldier equivalent of Captain America who was produced by the Soviet Union not relives his glory days in stories told to his fellow inmates and is mocked by his guards. He, in turn, leads them to their “mother,” who reveals that she was the scientist who worked on the beginnings of the mind control project. But can any members of this reunited not-really-a-family trust one another long enough to stop Dreykov?

Look, this is a Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe consumable product. You’ve already decided if you’re going to see it or not, and if you’re going to see it, whether you’ll do so on a big screen, fork over an exorbitant amount of money to watch it on Disney+, or wait for a more affordable at-home option. It exists to sell toys, costumes, and trips to theme parks while continuing to build the Disney monopoly that we should all be more worried about since the overseers of antitrust laws are asleep at the wheel, and probably would be more worried about if we weren’t all (a) contemplating our insignificance and powerlessness to stave off the climate disaster that will boil, drown, bury, burn, smother, etc. us all alive, or (b) living in a state of denial of said looming extinction event. Its emotional beats are rote, its storytelling checkpoints are familiar, and the forward thrust of its characters is largely moot considering that, as of 2019, Natasha Romanoff is dead. For what it’s worth, at least Disney isn’t trying to insultingly push Black Widow as “empowering for girls/women” (one can read the text that way, but it’s not part of the metatext for once, and the film itself calls attention to the fact that Natasha’s dark past as an assassin renders her “hero” status among “little girls” problematic, to say the least). This film is also decidedly Not For Children, given its use of the visual language we associate with human trafficking to illustrate the horrors of the Red Room as well as the higher-than-normal profanity and a fairly graphic verbal description of the Red Room’s sterilization procedure.

I’m sure that there will be some reviews that cite the film’s “heart,” although I would warn readers to take that with a grain of salt. The “reunited family that was really composed of spies but who could be a found family” element is present, and all of the cast (Pugh in particular) sell this angle in their performances, but how much it will resonate with you as a viewer will depend on a lot of factors that are external to the film proper. I wasn’t sold on it, but I still had a blast, and the setpieces here are some of the best that this franchise has brought to the table. Pugh is great in this first entry for her into the MCU, and Harbour brings an effortlessly comedic touch to the proceedings. Weisz has never given a bad performance ever, and her Russian accent here is a delight. It’s a shame that Johansson is finally given a vehicle in this series that is hers and hers alone and it must be an interquel due to the choices made in other films, but she’s been carrying films on her back since she was a literal child, so it’s no surprise that she delivers here in her postscript swan song. If you’re going to see it, see it, before we’re all dead.

-Mark “Boomer” Redmond